Dear Reader,

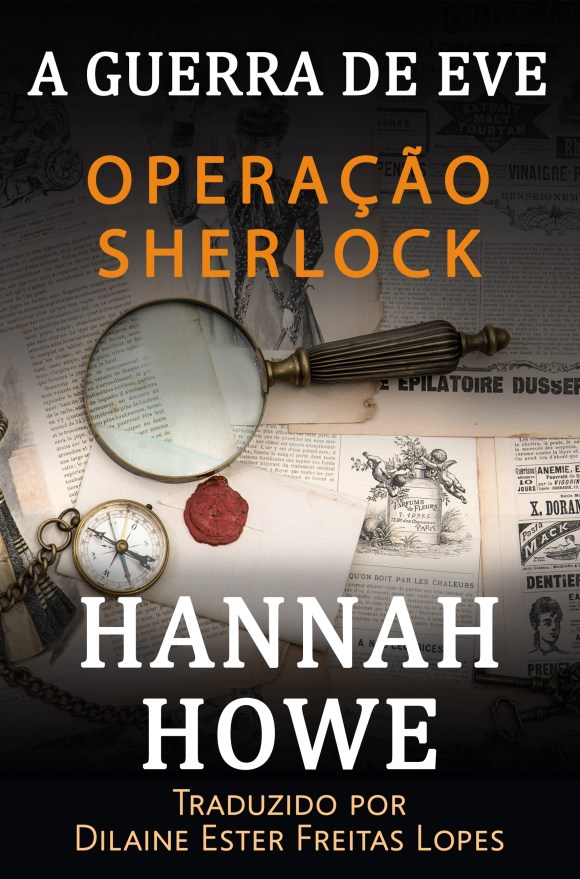

Always a satisfying moment, I’ve completed the storyboard for Operation Cameo, book six in my (Amazon #1 🙂) Eve’s War Heroines of SOE series. Next week, I will start on the first draft. Eve is feisty while her partner Guy is a pacifist. Based on true events.

My direct ancestor Joan, Countess of Kent (29 September 1328 – 7 August 1385) known to history as ‘The Fair Maid of Kent.’ French chronicler Jean Froissart described her as “the most beautiful woman in all the realm of England, and the most loving.”

Joan gave birth to my ancestor Thomas Holland and later when married to her third husband Edward Plantagenet ‘the Black Prince’, Richard II.

My direct ancestor Thomas Meade was born c1380 in Wraxall, Somerset. His parents were Thomas Atte Meade and Agnes Wycliff.

Thomas died in 1455 and this extract from his will offers an insight into the times.

“I leave to Philip Meade my son two pipes of woad, two whole woollen cloths, my beat goblet with a cover, made of silver and gilded, and my best brass bowl. I leave to Joan, the wife of Roger Ringeston, my daughter, one pipe of woad and 40s sterling.”

Lots of Quakers on my family tree. Here’s the latest discovery, Joan Ford, daughter of William Ford and Elizabeth Penny, born 11 December 1668 in Curry Mallet, Somerset. Joan was three years older than her husband, John Lowcock, not a big difference, but unusual for the era.

Just discovered that my direct ancestor Sir John Cobham, Third Baron Cobham, paid for the construction of Rochester Bridge (in the background on this painting) across the River Medway. This route, originally established by the Romans, was essential for traffic between London, Dover and mainland Europe.

Painting: Artist unknown, Dutch style, 17th century.

My 19 x great grandmother, Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester, was born in 1374, the only daughter of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, and his wife Isabella of Castile.

In November 1397, Constance married Thomas Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester, one of Richard II’s favourites. The couple produced three children: a son, Richard, and two daughters. The first daughter, Elizabeth, died in infancy, while the second daughter, Isabel, was born after her father’s death.

When Henry IV deposed and murdered Richard II, the Crown seized the Despenser lands. In consequence, in December 1399, Thomas Despenser and other nobles hatched a plot known as the Epiphany Rising. Their plan was to assassinate Henry IV and restore Richard, who was alive at this point, to the throne.

According to a French chronicle, Edward, Constance’s brother, betrayed the plot, although English chronicles make no mention of his role. Thomas Despenser evaded immediate capture, but a mob cornered him in Bristol and beheaded him on 13 January 1400.

After Thomas’ death, Constance was granted a life interest in the greater part of the Despenser lands and custody of her son. However, in February 1405, during the Owain Glyndwr rebellion to liberate Wales, Constance instigated a plot to abduct Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, and his brother, Roger, from Windsor Castle.

Constance’s plan was to deliver the young Earl, who had a claim to the English throne, to his uncle Sir Edmund Mortimer, who was married to Glyndwr’s daughter.

The first part of Constance’s plan went well, only to stumble when Henry’s men captured Edmund and Roger Mortimer as they entered Wales.

With the plot over, Constance implicated her elder brother, Edward – clearly sibling love was not a priority in the House of York – and he was imprisoned for seventeen weeks at Pevensey Castle. Meanwhile, Constance languished in Kenilworth Castle.

With the rebellions quashed, Henry IV released Constance and she became the mistress of Edmund Holland, 4th Earl of Kent. Out of wedlock, they produced my direct ancestor, Eleanor, who married James Tuchet, 5th Baron Audley.

Constance outlived Henry IV and her brother, Edward. She died on 28 November 1416 and was buried in Reading Abbey.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 31 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂