Dear Reader,

This week, I made great progress with the writing of Operation Rose, Eve’s War Heroines of SOE book seven, and Fruit, book four in my Olive Tree Spanish Civil War saga. Covid slowed me down over recent months, but this week was much more like it.

In this month’s issue of Mom’s Favorite Reads…

Crime and thriller author Shawn Reilly Simmons interviewed by Wendy H Jones. Plus, Author Features, Nature, Photography, Poetry, Short Stories, Young Writers, National Batman Day, and so much more!

You discover all sorts when you look through parish records.

My 3 x great grandmother Lucy Sarah Glissan was born in Stepney, London in 1842. In 1851 with her sisters Amelia, 13, and Mary Ann, 6, she was living in 28 Church Road, St-George-in-the-East, London in the shadow of this impressive Anglican church. Lucy’s parents were John Glissan, a surgeon/chemist/dentist and Sarah Glissan née Foreman, a nurse/chemist/dentist.

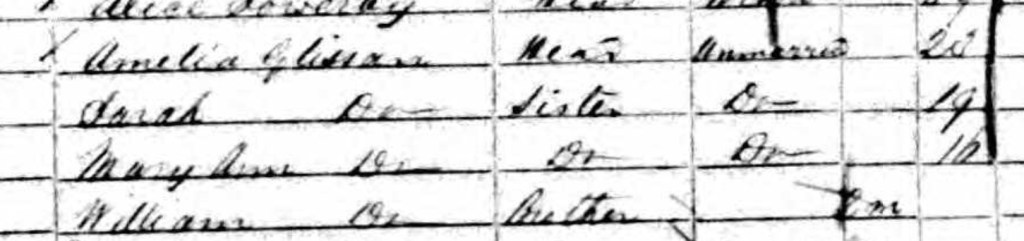

In 1861 my 3 x great grandmother Lucy Sarah Glissan, 19, was living with her sisters, Amelia, 23, and Sarah Ann, 16, in 2 Charles Street, St George-in-the-East, London. All three were unmarried tailoresses.

A baby also lived with the sisters, William, their ‘brother’. A problem: their mother, Sarah, was a widow of seven years and past childbearing age. To save face, the sisters had lied to the enumerator. So, which one of them gave birth to William?

The answer: my 3 x great grandmother Lucy Sarah Glissan. Shortly after the census was taken, Lucy Sarah married William’s father, Richard Stokes. Sadly, shortly after that William died. The couple produced seven more children including my direct ancestor William Richard Fredrick Stokes.

Lucy Sarah Glissan married Richard Stokes, who later ran a furniture-making business, at St Mary’s, Stepney on 27 May 1861. Both were nineteen, and literate. By 1870 80% of males were literate compared to 75% of females, up from 66% and 50% in thirty years. Lucy Sarah’s younger sister, Mary Ann, who witnessed the wedding, was also literate.

Lucy Sarah Glissan gave birth to eight children in twenty years 1861 – 1881. Her first and eighth child both died in infancy. The other six prospered. In the Victorian era the average number of children per family was six.

The Glissan sisters were close, so we should take a moment to explore Amelia and Mary Ann’s lives. Amelia married Charles Samuel, a mariner from Antwerp. The couple did not have any children. When Amelia died in 1894, Charles fell on hard times and entered the workhouse. Mary Ann married James Reynolds, a gun maker/engineer. The couple produced only one child, who died young.

Lucy Sarah died on 9 October 1888 at Red Lion Street, Shoreditch.

***

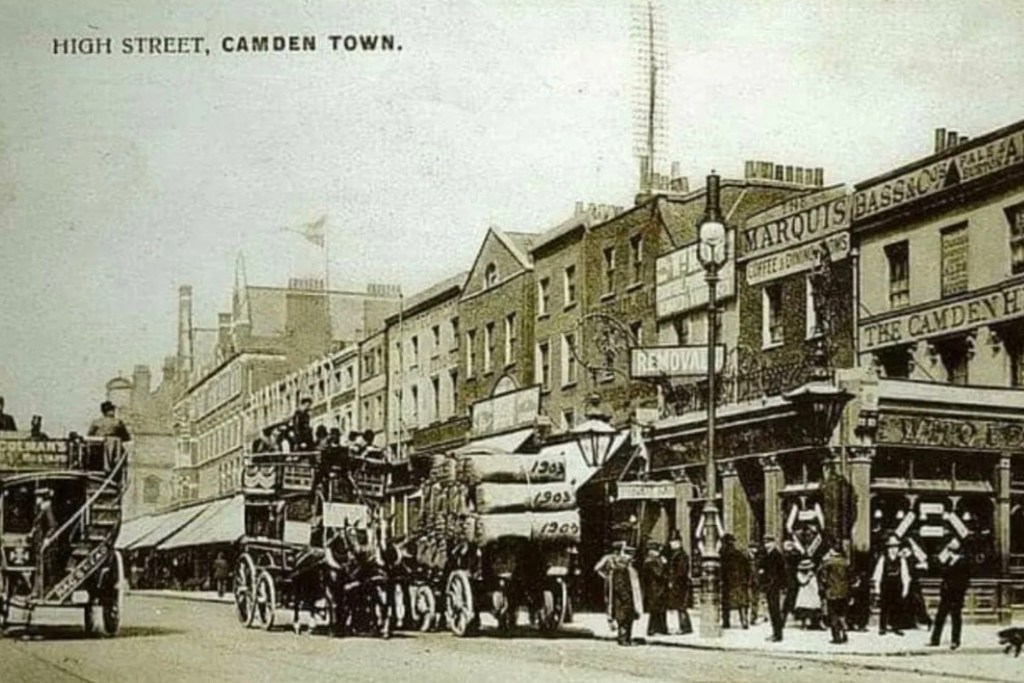

My 4 x great grandfather John Glissan was born in 1803 in Ireland. In 1824 Apothecaries Hall in Dublin recognised him as an apothecary with a licence to trade. A few years later, John moved to London where he found employment assisting John William Keys Parkinson, son of James Parkinson, the doctor who gave his name to Parkinson’s Disease.

Photographed in 1912 this is 1 Hoxton Square, London, the home and office of Parkinson and Son, surgeons and apothecaries. In the late 1820s my 4 x great grandfather John Glissan assisted the son, James, and added the skills of dentist and surgeon to his trade of apothecary. Picture: Wellcome Trust.

17 September 1829 a report in the London Courier detailing the evidence John Glissan, a surgeon, gave to an inquest into the death of Henry Kellard, a pauper.

In the early 1830s my 4 x great grandfather John Glissan left Parkinson and Son and set up his own business as a surgeon/chemist/dentist. Initially, he struggled and was forced to go on the road as a traveller, selling his medicines. In 1834 he was declared insolvent. Life for him in London was tough.

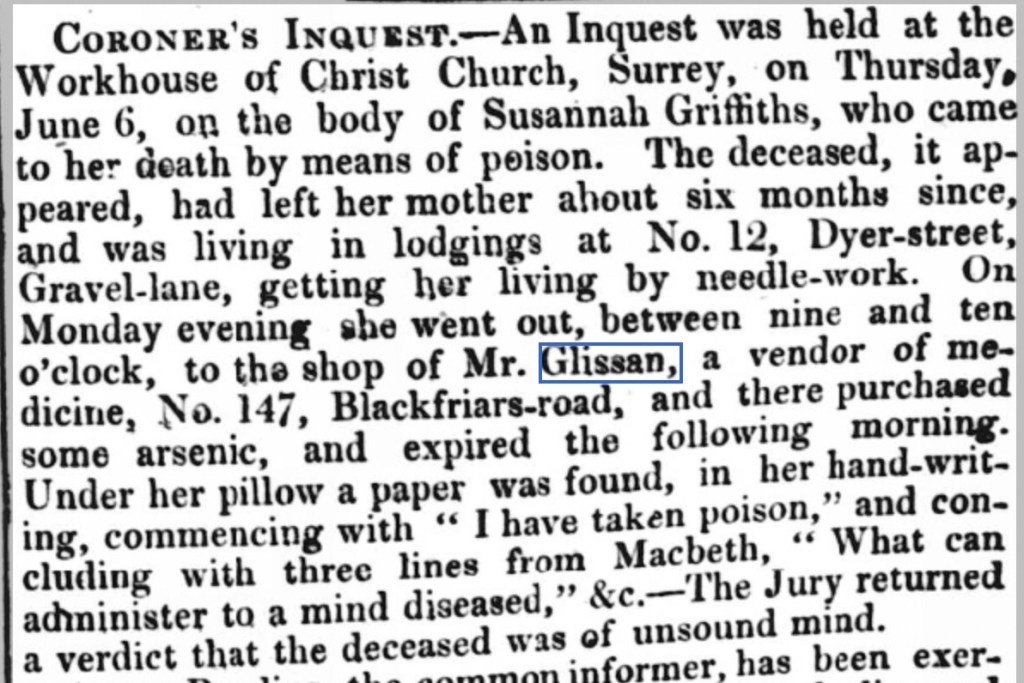

In early June 1833, at nine o’clock in the evening, Susannah Griffiths left her lodgings at 12 Dyer Street, London. She walked along George Street to the junction of Blackfriars Road, one of the most fashionable roads in nineteenth century London. She made her way to 147 Blackfriars Road and the shop owned by my 4 x great grandfather John Glissan. There, Susannah purchased a quantity of arsenic.

Returning home, Susannah set her needlework to one side and wrote a note, quoting Shakespeare’s Macbeth, “Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d, Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, Raze out the written troubles of the brain.” She added, “I have taken poison.” Then she placed the note under her pillow and swallowed the arsenic.

Susannah was educated. She understood Shakespeare. I imagine that she was a sensitive soul. A coroner’s inquest held at Christ Church Workhouse absolved John Glissan of any blame and concluded that Susannah died whilst being of unsound mind.

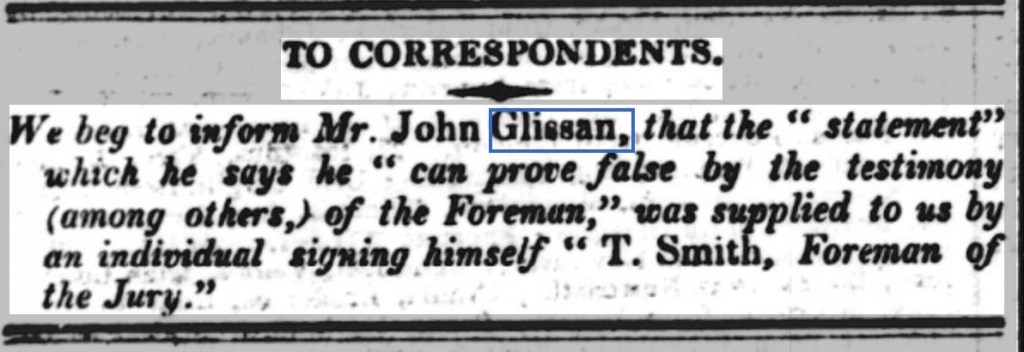

Two days after the newspaper report on Susannah’s tragic suicide, this mysterious message appeared in the Morning Advertiser. I’m not sure what to make of the note. There were no follow up messages, so I’m not sure what my ancestor John made of it either.

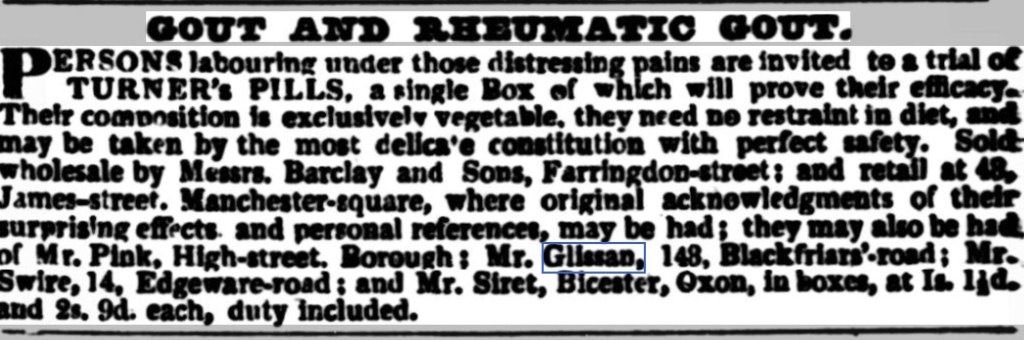

17 November 1833. If gout was your problem, my 4 x great grandfather John Glissan, a surgeon/dentist/chemist, was your man. In the 1830s, John appeared in many newspapers advertisements promoting potions for all manner of ailments.

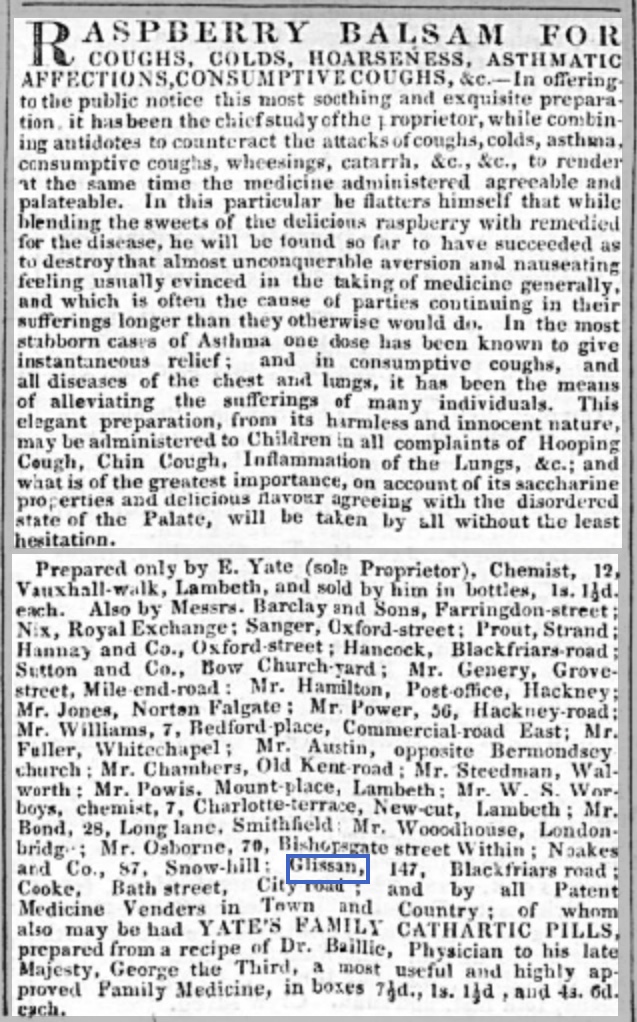

16 February 1834. Another advertisement featuring John Glissan. This advert ran on a regular basis in the Weekly True Sun.

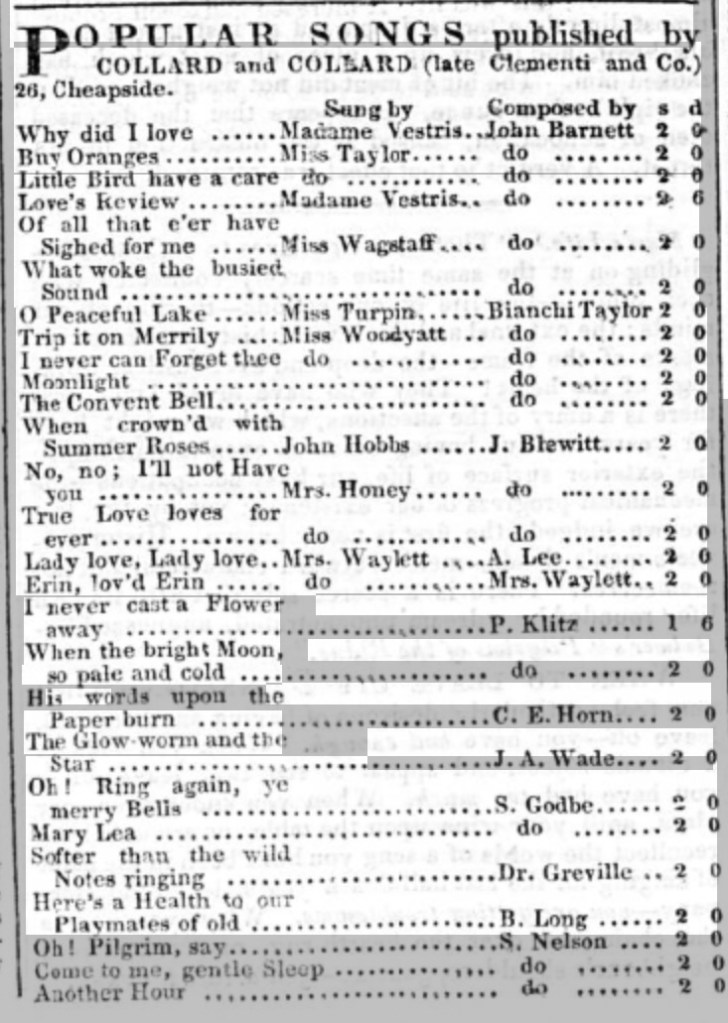

Top of the Pops, 16 February 1834. Note that female singers dominated. Madame Vestris (pictured) was Lucia Elizabeth Vestris (née Elizabetta Lucia Bartolozzi; 3 March 1797 – 8 August 1856) an actress and a contralto opera singer. She was also a theatre producer and manager.

For the first thirty years of his life John Glissan concentrated on learning the skills of a chemist, surgeon and dentist, and on establishing his business. In 1834, life offered a new challenge. More about that next time.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 32 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂