Dear Reader,

Preparing for 2022. The new year will see the continuation of my Sam Smith and Eve’s War series, the conclusion of my Olive Tree Spanish Civil War Saga, and the start of a new series, Women at War, five novels about ‘ordinary’ women fighting fascism in France, Spain and Bulgaria, 1936 – 1945.

Exciting news. My Sam Smith Mystery Series will be translated into Italian. We will make a start on Sam’s Song this week. As a European, I’m delighted that my books are available in twelve languages.

A rarity in the Victorian era, a husband’s petition for divorce, filed 16 November 1883. The husband stated that on ‘diverse occasions’ his wife committed adultery with ‘sundry persons’. Marriage dissolved. Damages awarded to the husband.

For Armistice Day.

My latest genealogy article for the Seaside News appears on page 36.

My direct ancestor Sir Edward Stradling was born c1295, the second son of Sir Peter de Stratelinges and Joan de Hawey. The exact location of his birthplace is unknown, but likely to be the family estates in Somerset.

When Sir Peter died, Joan married Sir John Penbrigg, who was granted wardship over Sir Peter’s estates and both young sons, Edward and his older brother, John, until they reached their twenty-first birthdays.

As an adult, Edward was Lord of St. Donats in Glamorgan, and Sheriff, Escheator, Justice of the Peace, and Knight of the Shire in Parliament for Somerset and Dorset. He rose to such prominence through his staunch support for Edward III.

Edward Stradling married Ellen, daughter and heiress of Sir Gilbert Strongbow. They produced the following children:

Edward (my direct ancestor) who married Gwenllian Berkerolles, daughter of Roger Berkerolles of East Orchard, Glamorgan.

John, who married Sarah, another daughter of Roger Berkerolles. Two bothers marrying two sisters.

When John died, c1316, Sir Edward inherited the following lands:

St Donat’s Castle, Glamorgan.

Combe Haweye, Watchet Haweye, Henley Grove by Bruton, Somerset, all of which included three messuages, a mill, five carucates, two virgates of land, thirty-one acres of meadow, and one hundred and forty-one acres of woodland.

Halsway and Coleford in Somerset.

Compton Hawey in Dorset.

Through his wife’s inheritance, he also obtained two manors in Oxfordshire.

As Lord of St. Donats, Sir Edward rose against the Crown in the Despenser War of 1321–22. The war was a baronial revolt against Edward II led by marcher lords Roger Mortimer and Humphrey de Bohun, fuelled by opposition to Hugh Despenser the Younger, the royal favourite.

The Crown arrested Sir Edward in January 1322 and seized all his lands in England and Wales. It took two years and a loyalty payment of £200 – £92,000 in today’s money – before his estates were restored.

When Edward II was deposed in 1327, Edward Stradling was knighted by Edward III. Several appointments followed, including Sheriff and Escheator of Somerset and Dorset 1343, MP for Somerset 1343, and Justice of the Peace for Somerset and Dorset 1346–47. On 11 September 1346, Sir Edward was one of three knights of Somerset at Edward III’s Westminster parliament.

Sir Edward was one of the chief patrons of Neath Abbey and on 20 October 1341 he gifted the monastery one acre of land. He died c1363, either in St Donats or Somerset.

The Strandling line continued through the second Sir Edward, born in 1318 in St Donats Castle to Sir William, born in 1365 in St. Donats, to another Sir Edward, born in 1389 in St Donats. This Sir Edward was Chamberlain and Receiver of South Wales, Sheriff of Somerset and Dorset 1424-6, Steward and Receiver of Cantreselly and Penkelly, Keeper of Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire (appointed 22 August 1439), Constable of Taunton 1434-42, and Knight of the Sepulchre.

Already well established amongst the nobility, the Stradling’s influence increased through the deeds of the third Sir Edward. He married Jane, daughter of Cardinal Beaufort, great uncle of Henry VI. This marriage ensured that he held a powerful position within the royal court.

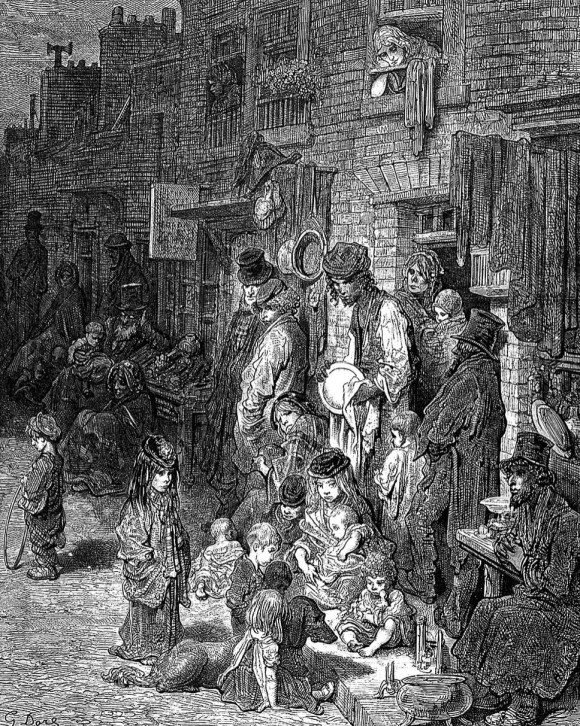

Administrative posts in South Wales and money followed. As with modern nobility, medieval nobility was a moneymaking-racket, a mafia, exploiting the poor. Lords and knights gave money to the Church to assuage their sins. Many lords were brutal and ruled through fear. Some, and I hope Edward was amongst them, used their positions of privilege and wealth to better their communities. For Edward these communities included parishes in Glamorgan, Somerset, Dorset and Oxfordshire. Of particular interest to me is the Stradling manor of Merthyr Mawr, a beautiful village, which is on my doorstep.

Sir Edward fought at Agincourt. He was captured by the French, and wool, a staple product of South Wales, was shipped to Brittany to defray his ransom.

In 1411, Sir Edward Stradling went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. In 1452, aged sixty-three, he went on a second pilgrimage, but did not return. He died on 27 June 1452 in Jerusalem.

To be a peasant or a noble in medieval times? Although I’m descended from noble houses, my inclination is to side with the peasants. Life is hard for the poor in any age, and it was certainly hard in medieval times. Against that, the nobles had to contend with political intrigues, treachery, wars and pilgrimages, from which many did not return.

Given a choice, I think I would select a middle course, neither peasant nor noble, but an observer, a chronicler, recording my life and times. After all, through fiction, that’s what I do today.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 32 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂