Dear Reader,

My latest translation in Portuguese, The Olive Tree: Roots. A Spanish Civil War Saga. Available soon 🙂

Many of my London ancestors came from Lambeth. This is the Thames foreshore at Lambeth, c1866, a photograph by William Strudwick, one of a series showing images of working class London.

My article about SOE heroine Eileen Nearne appears on page 36 of this month’s Seaside News.

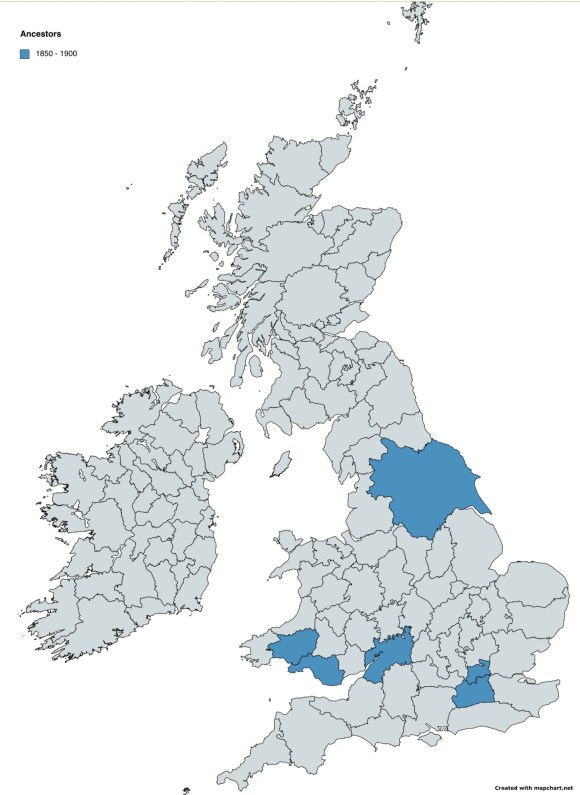

Mapping my ancestors over the past thousand years.

Map One: Twentieth Century.

My twentieth century ancestors lived in Glamorgan, London and Lancashire. My Glamorgan ancestors were born there while some of my London ancestors were evacuated to Lancashire during the Second World War where they remained for the rest of their lives.

Map Two: 1850 – 1900

Three new counties appear on this map: Carmarthenshire, Gloucestershire and Yorkshire. Yorkshire is represented by a sailor who lived in Canada for a while before settling in London. My Gloucestershire ancestors moved to London because they had family there, and no doubt they were looking for better employment opportunities. My Carmarthenshire ancestors moved to Glamorgan to work on the land, on the newly developing railway lines, and in the burgeoning coal mines. Some branches emigrated to Patagonia, but my direct ancestors remained in Glamorgan.

Published this weekend, Stormy Weather, book eighteen in my Sam Smith Mystery Series. My intention was to write one book, but I’m delighted that Sam convinced me to develop her story into a series 🙂

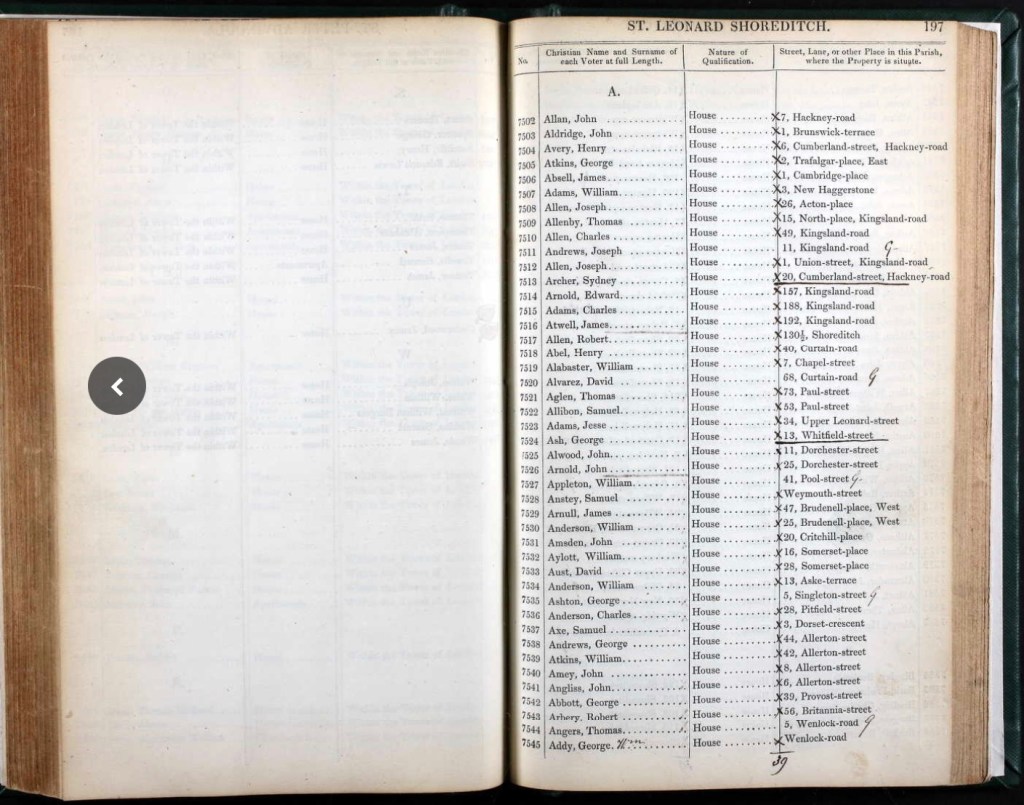

My 2 x great grandmother Jane Dent was baptised on 9 October 1870. The eldest daughter of Richard Davis Dent and Sarah Ann Cottrell, she lived in Whitechapel during the terror of Jack the Ripper.

The police investigated eleven brutal murders in Whitechapel and Spitalfields between 1888 and 1891. Subsequently, five of those murders were attributed to Jack the Ripper, those of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly, the murders taking place between 31 August and 9 November 1888.

The murders attracted widespread newspaper coverage and were obviously the major talking point within the Whitechapel community. What did that community look like and where did my ancestor, Jane Dent fit in?

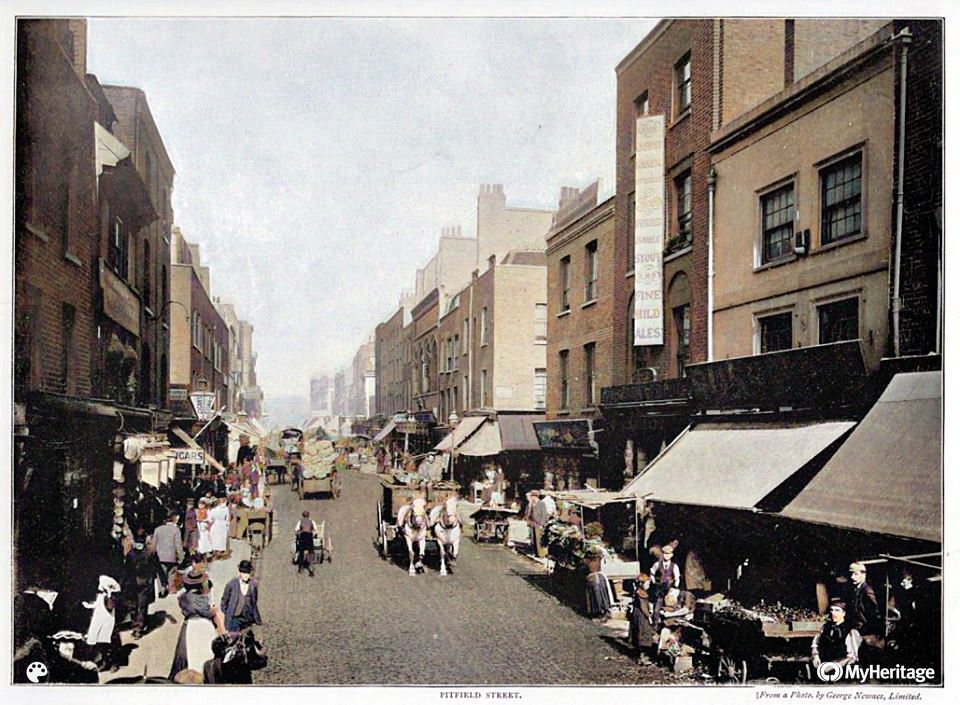

By the 1840s, Whitechapel had evolved into the classic image of Dickensian London beset with problems of poverty and overcrowding as people moved into the city from the countryside, mingling with an influx of immigrants. In 1884, actor Jacob Adler wrote, “The further we penetrated into this Whitechapel, the more our hearts sank. Was this London? Never in Russia, never later in the worst slums of New York, were we to see such poverty as in the London of the 1880s.”

In October 1888, Whitechapel contained an estimated six-two brothels and 1,200 prostitutes. However, the suggestion that all the Ripper’s victims were prostitutes is a myth. At least three of them were homeless alcoholics. The common thread they shared was they had fallen on hard times.

Jane’s father, Richard Davis Dent, died in 1883 when she was twelve so Jane lived in Whitechapel with her mother, Sarah Ann, and younger brothers and sisters, Thomas, Arthur, Eliza, Robert and Mary. The 1881 census listed Jane as a scholar, and it’s likely that she became a domestic servant after her schooling.

The Dent family lived in Urban Place. Their neighbours included a toy maker, a tobacco pipe maker, a French polisher, a vellum blind maker and a cabinet maker. These people were skilled artisans, so it wasn’t the roughest of neighbourhoods. Nevertheless, did Jane and her family discuss Jack the Ripper and his latest atrocities over the dining table? Almost certainly they did, and mothers throughout the generations have echoed Sarah Ann’s warnings to her daughters.

Did Jane meet Jack the Ripper, socially, at work or in the street? Possibly. Did she have a suspect in mind? Her thoughts were not recorded so we will never know. Did she modify her behaviour and avoid Whitechapel’s network of dark and dangerous allies? It is to be hoped that she did.

Although there are numerous suspects, from butchers to members of the royal family, it’s unlikely that we will ever discover Jack the Ripper’s true identity. The police at the time were led in the main by retired army officers, and were not the brightest detectives. Forensic science was basically unknown, so evidence gathering was limited. Nevertheless, the police’s failure to identify Jack the Ripper does raise some serious questions.

Was there a cover-up? It’s likely that members of the royal family did visit prostitutes – this is a common theme over many centuries – and the government would have issued instructions to the police to cover-up any royal association with prostitutes for fear of a public backlash and revolution, which was rife in parts of Europe. Any royal cover-up would have hampered the investigation, but ultimately Jack the Ripper evaded arrest because the Victorian police force did not have the skills required to solve complex murders.

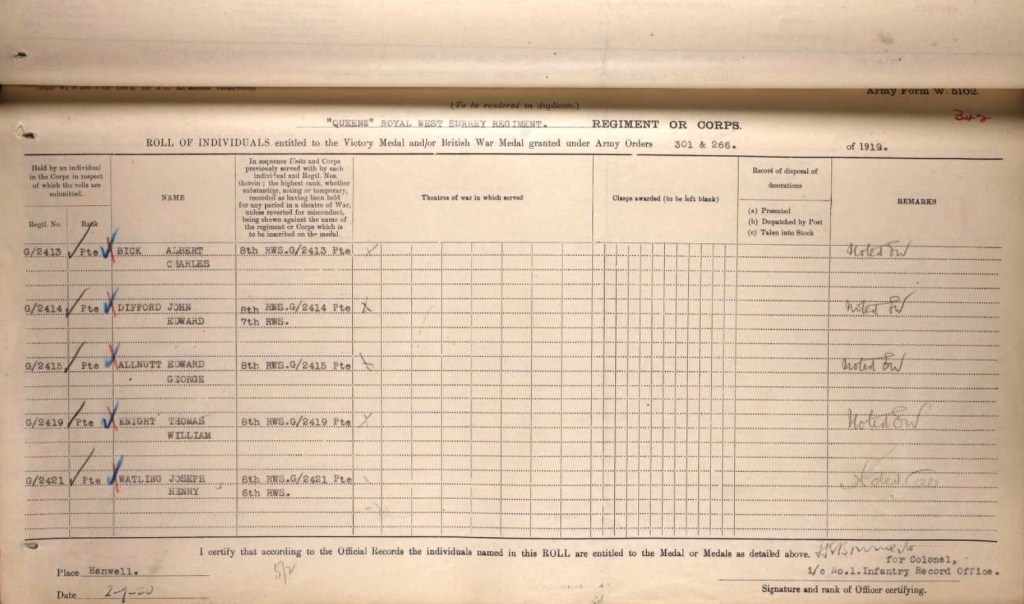

By 1891, the Whitechapel murders had ceased and Jane had married William Richard Stokes, a cabinet maker. The couple moved to Gee Street, in the St Luke’s district of London where they raised a family of nine children, including my direct ancestor, Arthur Stokes, and Robert Stokes who died on 26 June 1916 at Hébuterne, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France during the First World War.

Jane Dent survived the terror of Jack the Ripper, but memories of his murders must have remained with her for the rest of her life. After all, she was only eighteen years old, an impressionable age in any era. She died on 6 June 1950 in the London suburb of Walthamstow.

As for Jack, I suspect that either he took his own life in November 1888 or, unknown as the Ripper, he entered an asylum at that time, and remained there for the rest of his life. Jack the Ripper was a compulsive murderer. He didn’t stop killing, something stopped him.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

Bestselling psychological and historical mysteries from £0.99. Paperbacks, brand new in mint condition 🙂

https://hannah-howe.com/store/