Dear Reader,

I’m researching the Victorian era and my poverty-stricken London ancestors. This is a view of Whitehall from Trafalgar Square, 1839. Produced by M de St Croix, it’s one of the earliest daguerreotype photographs of England, taken when M de St Croix was in London demonstrating Louis Daguerre’s pioneering photographic process during September and December 1839.

In the foreground is Le Sueur’s statue of Charles I on horseback, and in the distance Inigo Jones’ Banqueting House – practically everything else has subsequently disappeared. The image has been reversed to show the scene as it was, as daguerreotypes only produce reversed views.

My direct ancestor Joan Plantagenet, daughter of Edward I of England and Eleanor of Castile. Joan was born in April 1272 in Akko (Acre), Hazofan, Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Joan has appeared many times in fiction, often depicted as a ‘spoiled brat’. There is no evidence that this depiction represents her true character, but the myth remains. That’s the power of fiction.

A lovely drawing of St Mary’s, West Bergholt, Essex, in the 1600s and 1700s the parish church of the Fincham, Balls, Clark and Sturgeon branches of my family.

My 4 x great grandmother Mary Ann Thorpe was baptised on 4 August 1816 in Great Braxted, Essex. The daughter of Thomas Thorpe and Mary Ann Freeman, she married Henry Wheeler on 3 November 1844 in St Mary, Lambeth, Surrey.

Mary Ann was Henry’s second wife. He was a petty thief. Also, she was eighteen years younger than him. Why did a young woman marry a far older, disreputable man? We will explore that question later.

Mary Ann and Henry produced four children: Mary Ann, Charlotte, Joseph and Nancy, my direct ancestor, who when married at sixteen changed her name to Annie. There was a nine year gap between Mary Ann’s birth and Charlotte’s birth. This pattern replicated Henry’s first marriage to Elizabeth Mitchell where there was a nine year gap between their first two children, Henry and Eliza. That marriage produced five children in total. Why the nine year gaps? Henry’s wives were clearly fertile, but he was not around. Where was he? Read on…

After each marriage and the birth of the first child, Henry resorted to petty crime to make ends meet. The family endured great hardship, extreme poverty, and with new mothers and babies to feed Henry became ‘light-fingered’.

At other times, Henry was no saint. His name features frequently in the criminal records. However, on many occasions he was found ‘not guilty’. Nevertheless, it’s clear that the Wheeler family lived their lives on the fringes of society and mixed with petty, and possibly, hardened criminals.

In 1845, after the birth of his daughter Mary Ann, Henry served a seven year prison sentence. The Victorians were keen on multiples of seven for their prison sentences, and this pattern extended to periods of transportation as well.

While Henry was in prison, his wife Mary Ann endured a difficult time. On 24 August 1849 it’s possible that she entered St Luke’s asylum. The records are sketchy, so it’s difficult to be certain, but the facts and circumstances fit so I am inclined to believe that she did spend some time in the asylum, maybe due to the burden of her circumstances.

Or maybe Mary Ann suffered from long-standing mental health issues. It’s possible that those issues made a match with a man her own age unlikely, hence her choice of Henry, the eighteen year older petty criminal. The psychological profile certainly fits. That said, maybe it was a love match. Love can still blossom even in the most dire of circumstances.

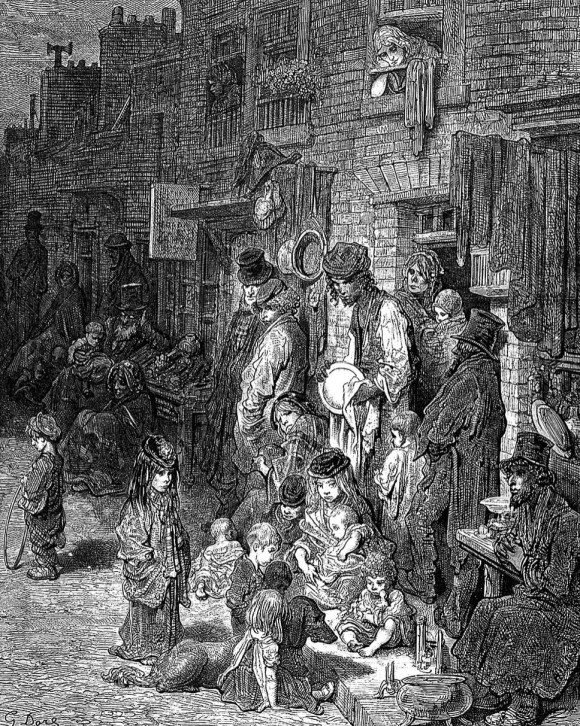

Earlier, on 20 September 1848, Mary Ann entered the workhouse, a foreboding institution that was more a place of punishment than support. The Victorian era through the Industrial Revolution generated great wealth, but that wealth was concentrated on a relatively small number of individuals. These people were extremely rich, but they treated the poor with contempt. We can see a parallel in our own times.

Mary Ann left the workhouse on 10 January 1849, but her troubles were far from over. She still had a baby to feed, no husband to call on, and a fight against the diseases poverty brings. For all her troubles Mary Ann was a strong woman and lived to be eighty-six.

Before exploring Mary Ann’s later years, first we must go back in time, to 3 February 1845 when she found herself following her husband’s well-trodden path to the Old Bailey.

Mary Ann was indicted for feloniously breaking and entering the dwelling-house of Susan Laws, on the 18 January 1845, and stealing two gowns, value 30s., the goods of Caroline Allen; and one shawl, 6s., the goods of Henry George Steer.

Caroline Allen, a dressmaker, gave evidence: she locked her door and went to bed late. In the morning, she discovered the door open and her possessions gone. She had no knowledge of Mary Ann. She also stated that two families and an old gentleman shared the dwelling-house.

John Robert Davis stated that he was a shopman to Mr. Folkard, a pawnbroker, in Blackfriars Road. On the 18 January, at half-past nine in the morning, Mary Ann pledged the stolen gown at the pawnbrokers and he gave her an inferior duplicate. He reckoned that Mary Ann made three shillings on the trade.

Police constable Michael Cregan stated that he visited Mary Ann’s lodging and found the gown and shawl hidden under bedclothes. The court also established that the main door was ‘broken open’ although there were no marks of violence. The conclusion was that someone had used a skeleton key.

Eliza Beale, a fellow lodger, stated that she knew Mary Ann and that she was ‘an unfortunate girl.’ – An observation on Mary Ann’s mental health? Crucially, Eliza added that she came home at four o’clock in the morning when a man and woman asked her if she knew where they could get a bed. She let them into her room. They had a bundle with them, but she did not see them the following morning.

Martha Winfield, the landlady, contradicted Eliza Beale. However, Martha did not live in the house and therefore she was not an eyewitness to the events that night. Her contradiction was based on opinion, not on fact.

Verdict: Not Guilty.

In her closing years, as a widow, Mary Ann lodged with other elderly people. Over her eight-six years she certainly witnessed the darker aspects of London life. She also witnessed a period of dramatic change. At no stage was Mary Ann’s life easy. But she battled through and her life stands as a testimony to the human spirit.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 31 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂