Dear Reader,

My latest article for the Seaside News.

The teleplay for Exit Prentiss Carr, Series 1, Episode 4 of The Rockford Files, was written by long-standing Rockford Files associate Juanita Bartlett (pictured).

This episode was set in the fictitious town of Bay City. Raymond Chandler set his 1940 novel Farewell My Lovely in Bay City, so presumably Exit Prentiss Carr was a homage to Chandler. Bay City also appeared in season two of The Rockford Files.

James Garner appeared in every scene in this episode. When that happens in detective fiction I think it makes for a stronger story, but obviously it’s quite demanding for the lead actor.

In the late sixteenth century, London had four regular companies and six permanent playhouses with plays performed every day except Sunday. The plays were popular with rich and poor alike with prices set to attract lower paid workers.

The authorities loathed the playhouses because people could gather together in large numbers while the plays themselves often challenged authority, a combination that offered the potential for civil unrest.

🖼 Bankside c1630, the earliest known oil painting of London. The theatres depicted on the south bank are the Swan, the Hope, the Rose, and the Globe. The flying flags indicated that there was a performance that day.

In the 1620s there were 400 taverns and 1,000 alehouses in London. Writing in 1621, Robert Burton said, “Londoners flocked to the tavern as if they were born to no other end but to eat and drink.”

Cookshops provided roast dinners and pies, and takeaways. Hawkers sold shellfish, nuts and fruit while if you fancied a cheesecake Hackney was the place to go, and Lambeth was noted for its apple pies.

🖼 The Tabard Inn, renamed The Talbot, one of 48 inns or taverns situated between King’s Bench Prison and London Bridge, a distance of half a mile.

In 1642 Londoners rebelled against Charles I and he left town. The Civil War of 1642-49 was destructive, of course, but it did have some benefits. John Evelyn noted that when the supplies of hearth coal from Newcastle were interrupted London’s orchards and gardens bore ‘plentiful and infinite quantities of fruits.”

During the Civil War, London did not witness any major fighting, primarily because the Parliamentarians controlled the capital from an early stage. Without London, Charles I was doomed to defeat.

On the whole, city leaders were pro-Royalist while the workers sided with the Parliamentarians. However, by 1661 the workers were happy to welcome the new king, Charles II. The moment was lost, and Britain never recovered.

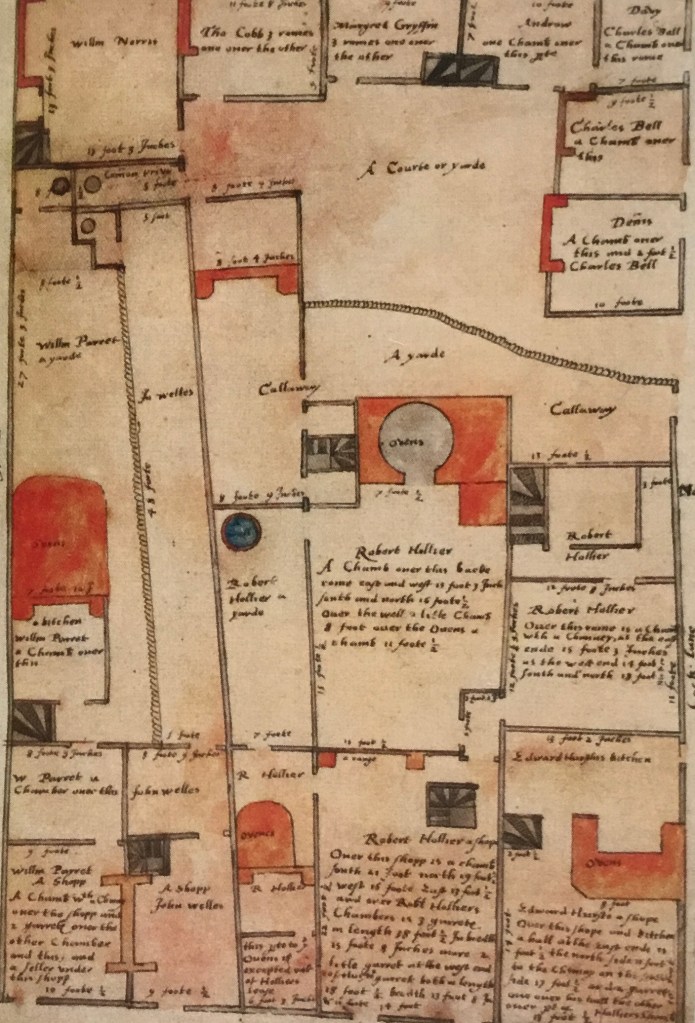

🖼 George Vertue’s plan of the London Lines of Communication, 1642.

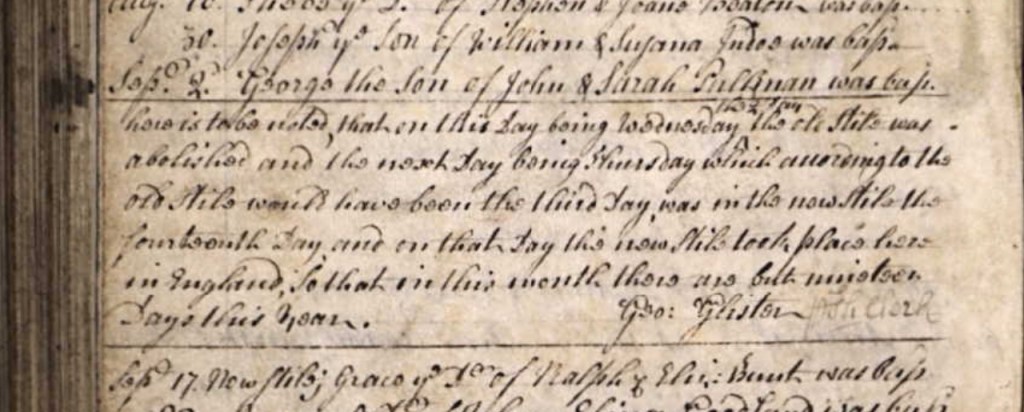

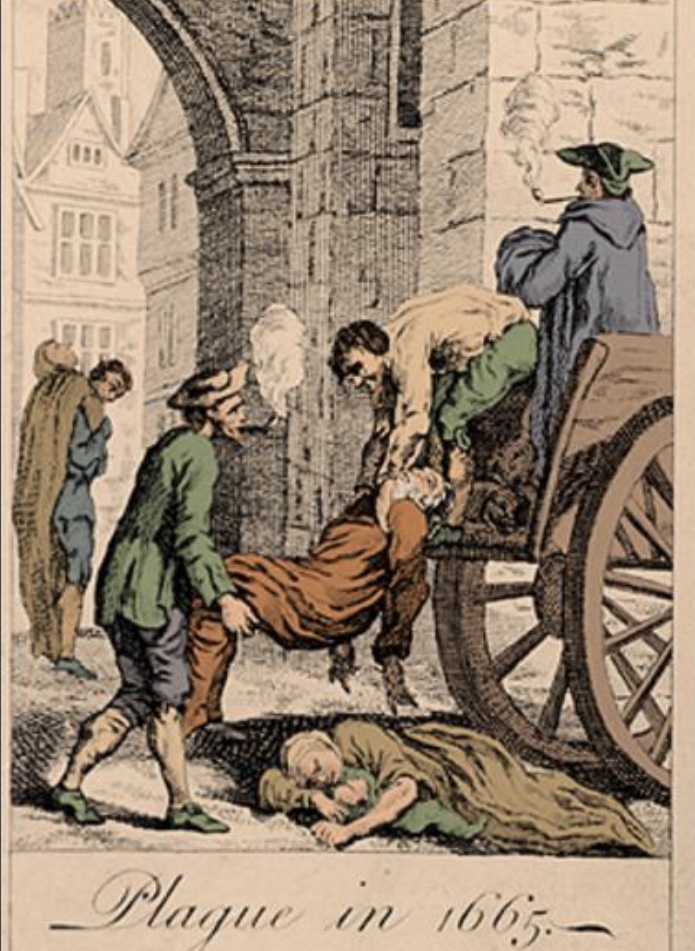

Plague visited London in 1665. By the end of the year over 100,000 people were dead, a fifth of the population. The plague began just before Christmas 1664 when two men in Drury Lane died of ‘spotted fever’.

By May 1665 the plague had spread to most of London’s 130 parishes and those who could afford to fled. Trade declined. The highways were clogged with refugees. Thomas Vincent remained in London throughout the plague. He noted that death rode ‘triumphantly on his pale horse through our streets and breaks into every house almost where any inhabitants are to be found’.

The authorities established ‘pest houses’ in fields and open spaces in an attempt to segregate the infected from the able-bodied. At the peak of the epidemic, mid-August to mid-September 1665, 7,165 people died in one week. Under such strain, traditional burial practices were abandoned in favour of common graves.

A Bill of Mortality published at the plague’s peak included the following as cause of death: Aged, 43. Burnt in his bed by a candle, 1. Constipation, 134. Flox and Smallpox, 5. Frighted, 3. Falling from a belfry, 1. Kingsevil, 2. Lethargy, 1. Rickets, 17. Rising of the Lights, 11. Scurvy, 2. Spotted Fever, 101. Stillborn, 17. Teeth, 121. Winde, 3. Wormes, 15. Plague, 7,165.

Males christened that week, 95; females, 81. Males buried, 4,095; females, 4,202. Parishes clear of the plague, 4. Parishes infected, 126. Many people returned to London in December 1665. However, members of parliament did not return until the following spring.

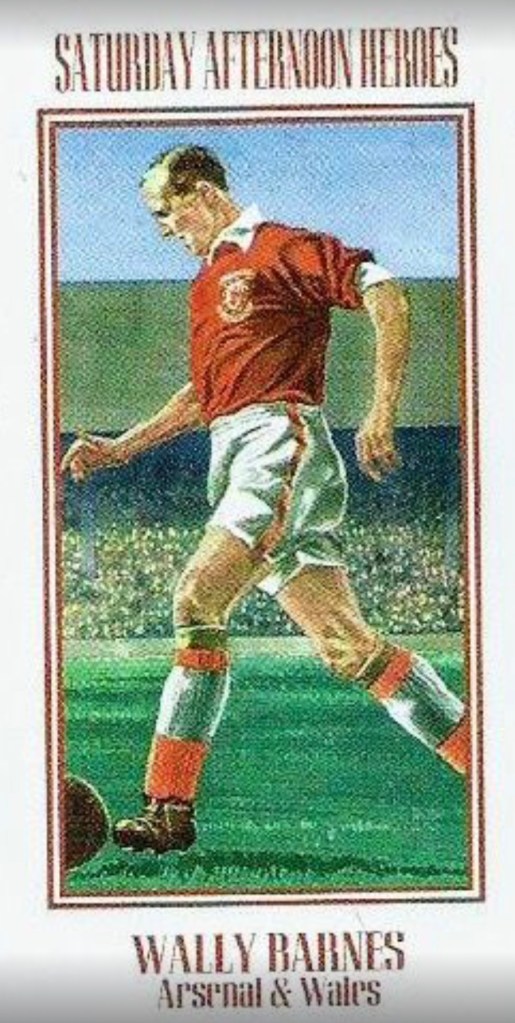

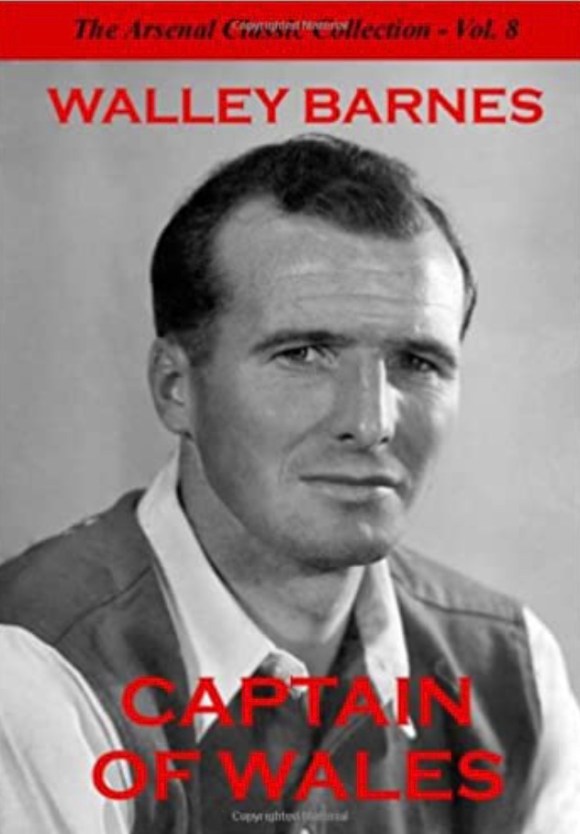

Welsh Football Legends

Walley Barnes was born on 16 January 1920 in Brecon, Wales. His parents were English. They were living in Brecon because Walley’s father, Edward, an army physical education instructor and footballer, was stationed with the South Wales Borderers.

Walley’s footballing career began during the Second World War. Initially, he played inside-forward for Southampton making 32 appearances between 1941 and 1943, scoring 14 goals. Walley’s impressive strike rate attracted the attention of Arsenal and he signed for the London club in September 1943.

At a time of ‘make do and mend’ footballers were versatile too. He played in virtually every position, including goalkeeper. In 1944 a serious knee injury threatened his career and an early retirement seemed a distinct possibility. However, Walley recovered, played in the reserves and forced his way back into first-team reckoning.

On 9 November 1946, Walley made his league debut for Arsenal against Preston North End. By 1946 he’d settled into his regular position of left-back. He won praise for his assured performances, his skilful distribution and his uncanny ability to cut out crosses.

A regular in the Arsenal team that won the First Division Championship in 1947-48, Walley enjoyed more success in 1949-50 when Arsenal defeated Liverpool in the FA Cup final. On that occasion, deputising for injured captain Laurie Scott, Walley played right-back.

In the 1951-52 FA Cup final Walley injured a knee. He left the pitch after 35 minutes and missed the entire 1952-53 season, which saw another league triumph for Arsenal. Thereafter, his first-team appearances became more spasmodic.

After only eight appearances in 1955-56, Walley retired. In all he played 294 matches for Arsenal and scored 12 goals, most from the penalty spot.

For Wales, Walley won 22 caps and captained his country. He made his debut against England on 18 October 1947, marking Stanley Matthews. Matthews and England got the better of Wales that day and won 3 – 0. England also won the British Home Championship that year while Wales finished a creditable second.

As Walley’s playing career faded, he turned to management. Between May 1954 and October 1956 he managed Wales. Notably, on 17 July 1958 he signed a letter to The Times opposing the ‘policy of apartheid’ in international sport and defending ‘the principle of racial equality, which is embodied in the Declaration of the Olympic Games’.

Walley joined the BBC and presented coverage of FA Cup finals. With Kenneth Wolstenholme, he was a commentator on the first edition of Match of the Day, broadcast on 22 August 1964. He also provided expert analysis in the live commentary of the 1966 World Cup final when England beat West Germany 4 – 2.

Walley wrote his autobiography, Captain of Wales, which was published in 1953. He continued to work for the BBC until his death on 4 September 1975.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 32 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂