Dear Reader,

It’s very satisfying when readers enjoy your books and this comment about Eve’s War: Operation Locksmith is particularly pleasing. “The writing has such historical authenticity it made me feel as though Eve had written her own story. Highly recommended.” 🙂

The brave Americans who fought fascism in the Spanish Civil War. “Somebody had to do something.”

A Mercedes 35 hp motor car, 1901. Designed by Wilhelm Maybach and manufactured by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft of Cannstatt, Germany, these cars achieved great success in the early years of motor racing.

The Eiffel Tower under construction, 1887-1889.

An example of the sabotage work undertaken by my SOE agents Eve, Guy and Mimi in my series Eve’s War Heroines of the SOE.

One of the great deception plans of the Second World War. British soldiers moving inflatable tanks on the south coast, 1944. The idea was to confuse the Nazis about the size of British forces and the D-Day landing zones. Amazingly, the plan worked.

Ancestry

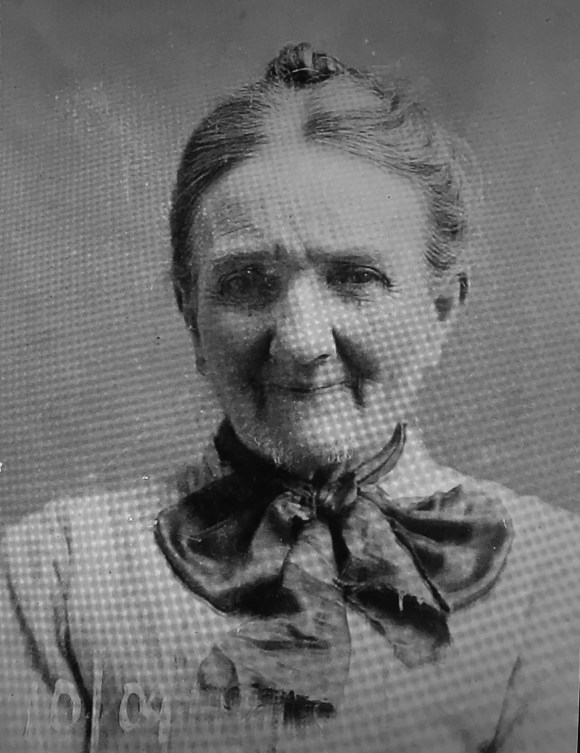

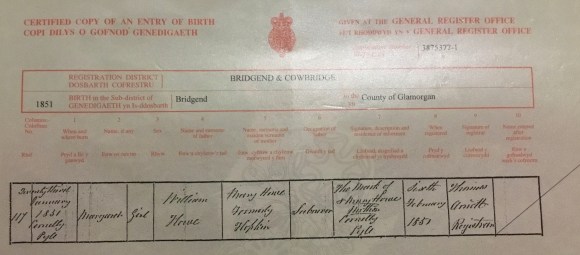

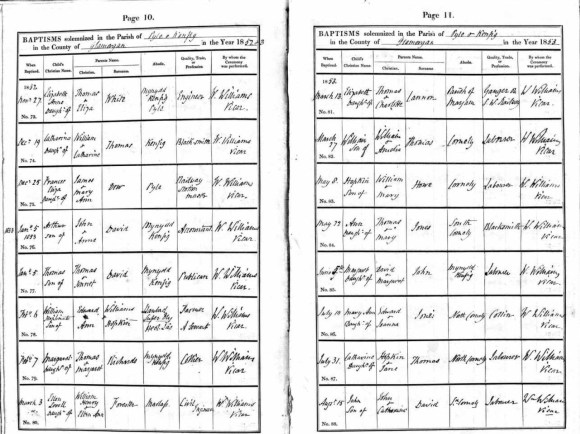

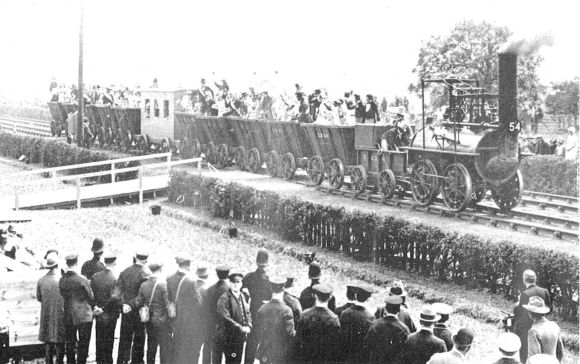

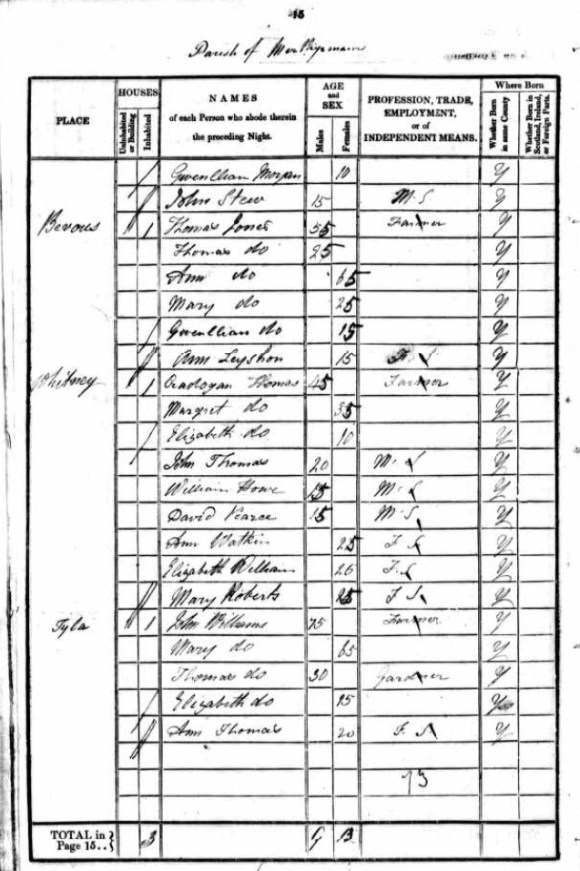

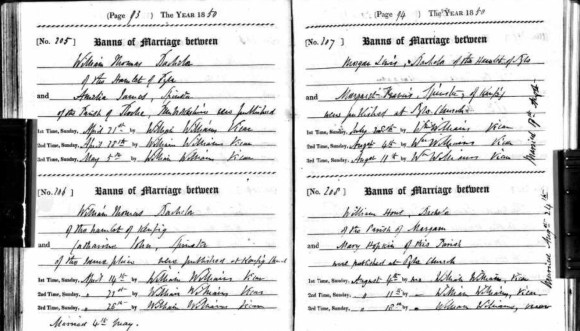

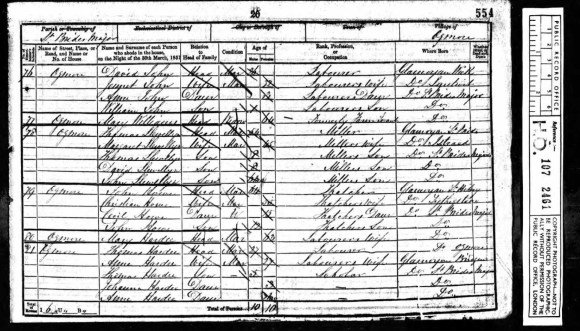

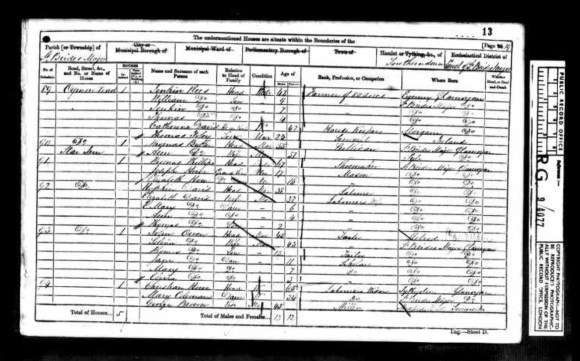

My 2 x great grandfather, William Howe, married Ann Jones in 1878 and they had nine children. However, before exploring their lives there is a mystery to solve: why was their nine year old niece, Elizabeth Burnell, living with them in the 1880s?

Elizabeth Burnell was the daughter of Ann’s sister, Mary Jones and Thomas Burnell. Elizabeth had three sisters, Mary Ann, Louisa and Esther, so to unlock the mystery we must explore the records associated with the Burnell’s.

The son of John Burnell and Elizabeth Poole, Thomas Burnell was born on 13 September 1846 in Minehead, Somerset. John was a farm labourer and Thomas began his working career aged fourteen as a plough boy.

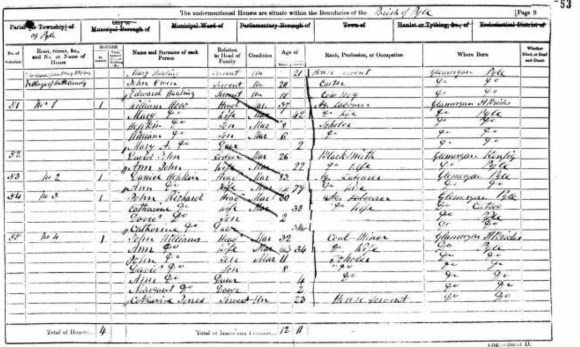

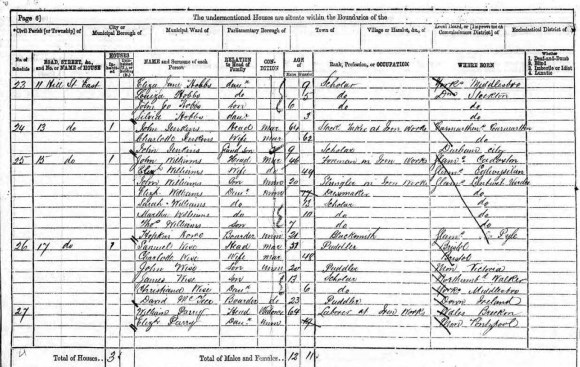

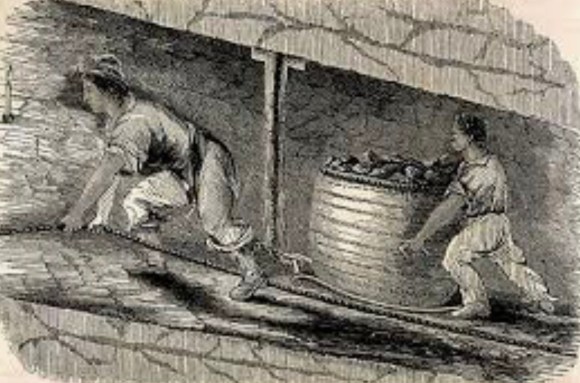

In his early twenties, Thomas made his way to Wales, to the New House Inn in North Corneli to be exact, where he lodged while working as a haulier, a miner responsible for transporting coal within a coal mine. We are in the 1870s and Thomas is one of thousands of men who have arrived in the South Wales Valleys to mine the ‘black gold’, the rich seams of coal.

During the summer of 1871, Thomas found himself in Newton-Nottage. It’s highly likely that he was working on the land as an agricultural labourer at this time and that he met Mary Jones there because she was working as a servant at Grove Farm, Newton-Nottage.

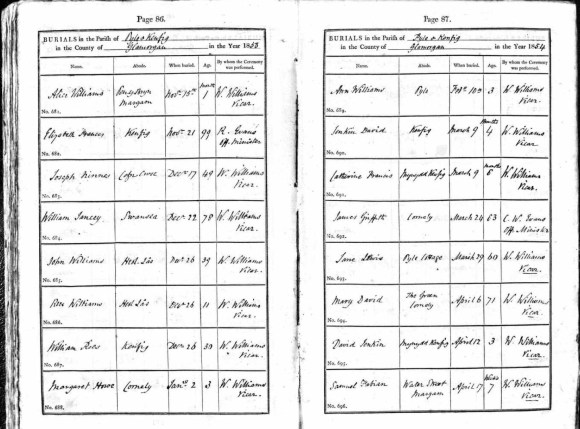

Thomas and Mary married on 12 September 1871 at the parish church of Newton-Nottage. Thomas was a labourer, which confirms that he returned to the land. They signed their names with a mark, as did their witnesses, Evan Lewis and Jane Hughes. Evan was Mary’s half-brother and Jane was, presumably, a friend.

Thomas and Mary’s four daughters were born in 1872, 1873, 1877 and 1879. The gap in 1875 is suspicious. Did Mary miscarry that year, or was she and Thomas living apart for some reason? Thomas had returned to the coal mines as a coker and was living in various locations as he sough employment. In normal circumstances, his wife Mary would have moved with him.

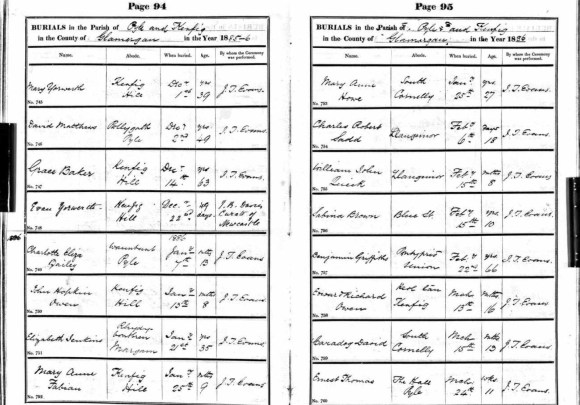

While Elizabeth lived with my 2 x great grandparents, William and Ann, Mary’s other children, Mary Ann, Louisa and Esther, moved around the South Wales coalfield with their father, Thomas. Meanwhile, where was Mary?

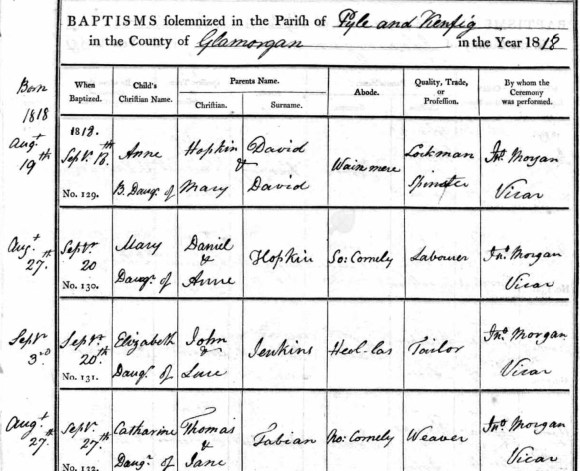

Mary was born c1849 to David Jones and Ann David. She had an older half-brother, Evan Lewis, and a younger sister, my 2 x great grandmother, Ann Jones. Therefore, a small family for the Victorian era.

Mary’s father, David, a labourer, was 51 when she was born, while her mother, Ann, was 37. There is a disjointed feel to this branch of my family, with many gaps in the historical record, inaccuracies with ages and unconventional relationships. I sense that these people were struggling for companionship and materially to survive.

Mary Jones gave birth to Esther Burnell on 5 June 1879 at the Level Crossing, Ty Newydd, Llangeinor. Esther’s birth wasn’t registered until 14 July 1879, which suggests Mary was not well after the birth. I’ve managed to track down her full medical record and it reveals that she was indeed ill, so ill in fact that she had no option other than to enter the local asylum.

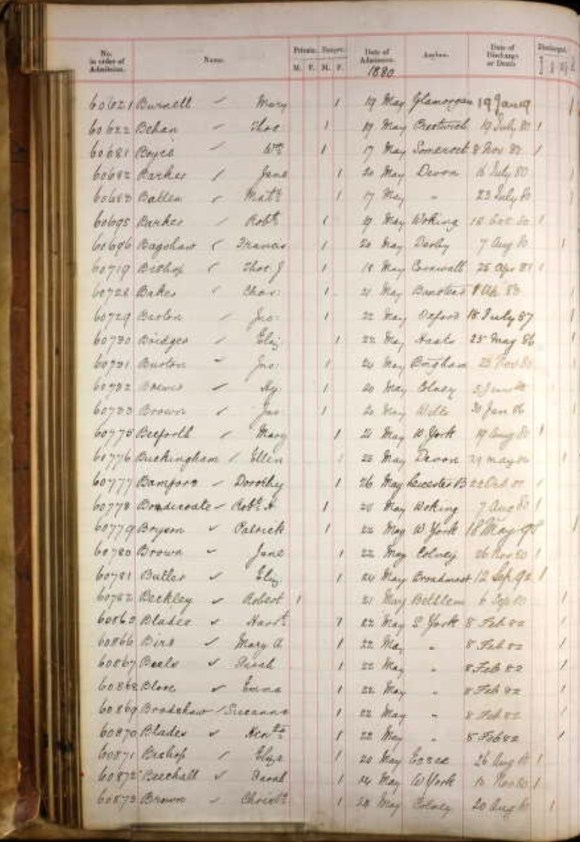

Mary Burnell was admitted to Angelton asylum on 19 May 1880, aged 29. A collier’s wife, her location was listed as Bridgend and Cowbridge, which suggests that her family was constantly on the move in search of employment.

Mary’s medical record states that her first ‘attack’ was of seven days duration the cause ‘probably puerperal’ and therefore related to the birth of her fourth daughter, Esther. The doctors did not regard Mary as epileptic or dangerous, but they did list her as suicidal because she tried to throttle herself. Also, her husband Thomas had to lock up all knives, ropes and ‘other articles with which she could have destroyed herself.’

At this stage, Mary had been ‘dull’ for four months, ten months after Esther’s birth.

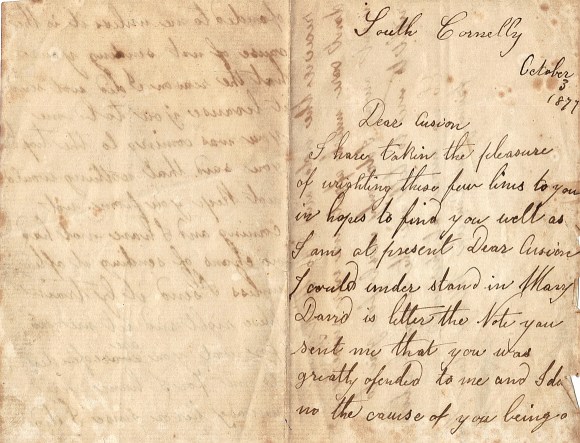

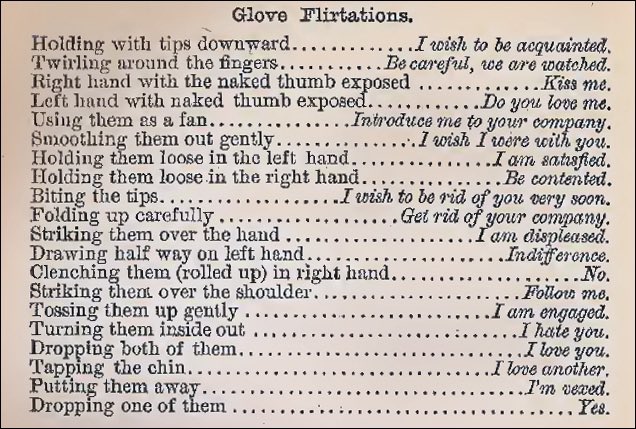

Mary’s medical record states that, ‘She says she has committed a sin against the almighty for which she will not be forgiven. And that she is eternally lost and that I have sold her to the Devil.’

Mary was admitted on 19 May 1880, but she was in the asylum on 20 and 27 April when she ‘slept a little, took food, but was very dull and miserable.’

In May, Mary passed the time with her sewing. However, she experienced a major psychotic episode on 9 May when she cried loudly and threw herself on the ground. She imagined that she was a snake and had married the Devil instead of her husband.

This pattern of sewing and disturbing delusions continued throughout the summer.

In September 1880, Mary stated that she had ‘done something seriously wrong.’ Her behaviour was good, but sometimes she could be ‘silly’.

There was no change in Mary’s condition for over a year. On 11 February 1882 she broke some windows and cut her hand. Was this a suicide attempt? The doctors didn’t think so and made no mention of attempted suicide in their notes.

The note dated 12 December 1883 is potentially revealing. ‘This woman is rather reserved, getting into solitary corners apart from her neighbours. Her memory is deficient and her morals have apparently been loose.’ Could this imply that Thomas was not Esther’s father and that the birth triggered guilt about an affair followed by a psychotic reaction?

By June 1884, Mary had become, ‘A rather troublesome woman, often interfering with others and at times destructive. Very demented.’ This pattern of behaviour continued until December 1885 when Mary settled down.

However, by June 1886 Mary was ‘foolish’ again. She suffered from housemaid’s knee throughout the summer. The nurses bandaged her knee, but she kept on removing the bandage. Nevertheless, her knee healed.

On Christmas Eve 1886, Mary stated that she had been in the asylum for eight years. In reality she had been there for six years. She also stated that she had been in Heaven and that it was a room with glass walls, which housed Jesus. She was industrious and always kissed the floor after washing it.

As the years rolled on, the pattern continued. The staff at the asylum regarded Mary as a good worker who saw herself as sinful. She heard voices at night from the spirits in the loft and regarded the other patients as her sheep.

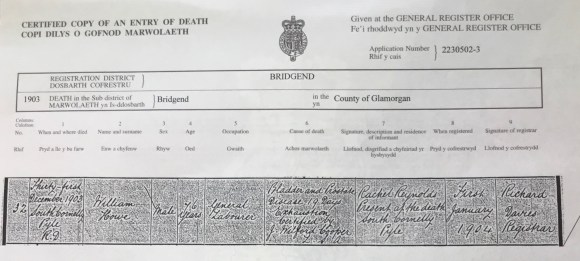

While Mary suffered in the asylum, her husband Thomas Burnell continued to work in the coal mines. He needed help to look after his children and enlisted Mary Williams as a ‘housekeeper’. However, the couple soon became lovers and in the space of eight years produced five children. Obviously, Thomas had decided that his wife Mary would never leave the asylum and that he had to get on with his life. The hard graft of coal mining took its toll on his health, however, and by 1896, at the age of fifty, he was dead.

On 24 September 1889 while working in the kitchen, Mary threatened to ‘cut her little head off’ twice during the day. As a result, the staff confined her to the ward under constant supervision.

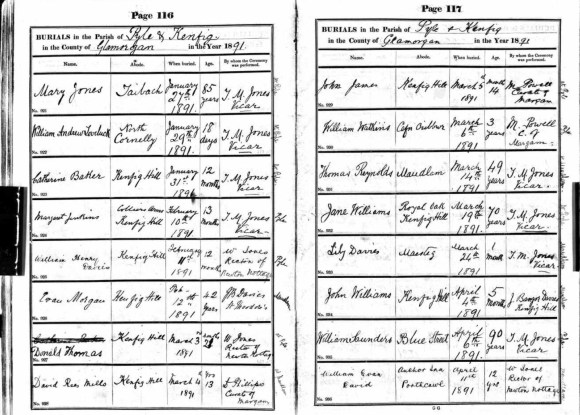

On 7 February 1891, the doctors transferred Mary to Parc Gwyllt, a new hospital that housed patients deemed incurable. After eleven years of psychiatric care the doctors decided that Mary’s condition would not improve.

By 1896, Mary’s profanity and sexual delusions were becoming more pronounced, which resulted in regular obscene outbursts. This pattern continued for the next seven years.

During January 1903, Mary was ill with influenza and an attack of facial erysipelas. She made a good recovery and returned to stable physical health.

In August 1908, Mary imagined that she was married to Samuel Butler, 4 December 1835 – 18 June 1902, author of the semi-autobiographical novel, The Way of All Flesh, a book that attacked Victorian hypocrisy. At this point, Mary called herself Mary Burnell-Butler. Butler never married. Indeed, he had a predilection for intense male friendships, which are reflected in several of his works. One wonders why Mary felt attracted to him.

The final entry in Mary’s medical record, dated 20 January 1909, stated that she was ‘mentally feeble’ and suffered from auditory hallucinations.

Aged 67, Mary died on 19 January 1919 at Parc Gwyllt of heart disease, ‘duration unknown’. Her death certificate also acknowledged that she suffered from dementia.

Mary’s daughter, Elizabeth, left my 2 x great grandparents home to nurture her own family. In 1891 she married William Cocking and the couple had six children.

And what of Esther? After a tough upbringing she established herself in the world. At the turn of the century, she moved to Cardiff where she was employed as a servant, looking after a middle-aged man, Aaron Rosser. The 1901 census described Aaron as an ‘imbecile’. Undoubtedly, Esther knew about her mother and decided that the goal in her working life was to help others less fortunate than herself.

Mary’s sins, were they imagined or real? To Mary, they were real, yet her medical notes make no mention of any facts to suggest that she had sinned. In the Victorian asylum, therapies were basic with little hope of offering a cure. Mary worked and the asylum provided food and a bed, but for 39 years she suffered with her delusions, her mistaken beliefs born out of physical illness, the attitudes of a deeply religious community and a susceptibility to mental health problems doubtless inherited from her ancestors.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx