Dear Reader,

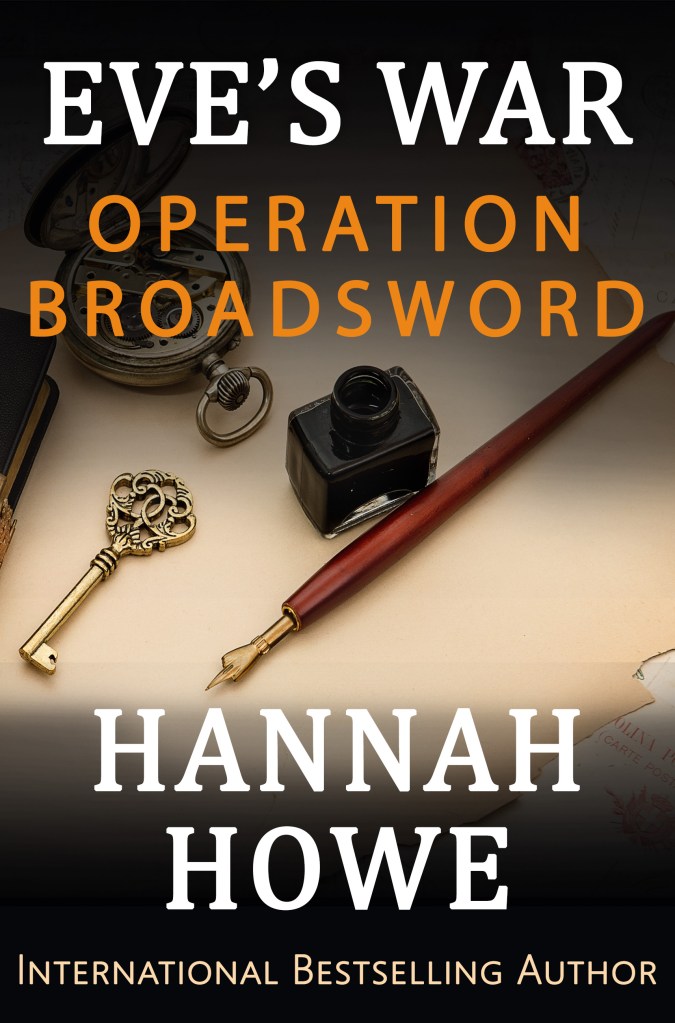

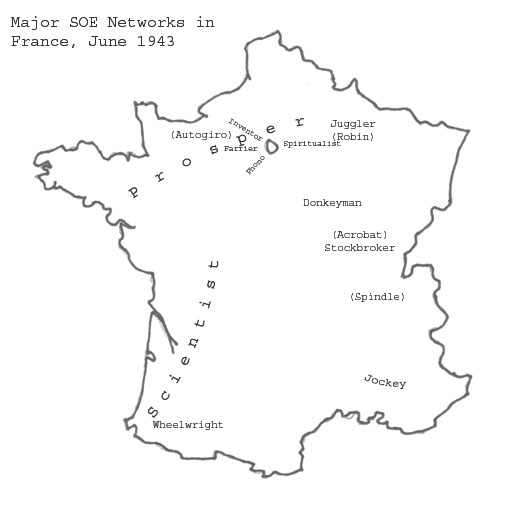

I’ve received messages asking me when Operation Cameo, book six in my Eve’s War Heroines of SOE series, will be available. I’m pleased to say that the book will be listed on all major platforms as a pre-order later this month.

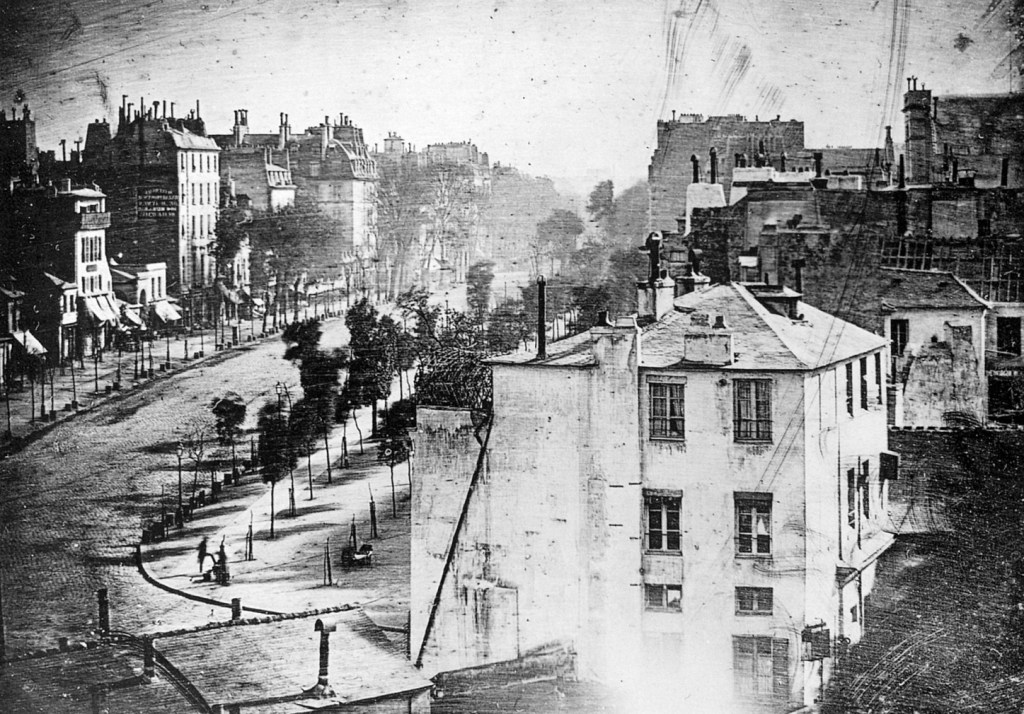

The earliest photograph to feature people. The Boulevard du Temple 1838 by Louis Daguerre. Because the exposure lasted for several minutes the moving traffic in the busy street left no trace. Only a shoe polisher and his client remained in place long enough to appear on the printed image. Sam mentions this in my latest Sam Smith mystery, Damaged.

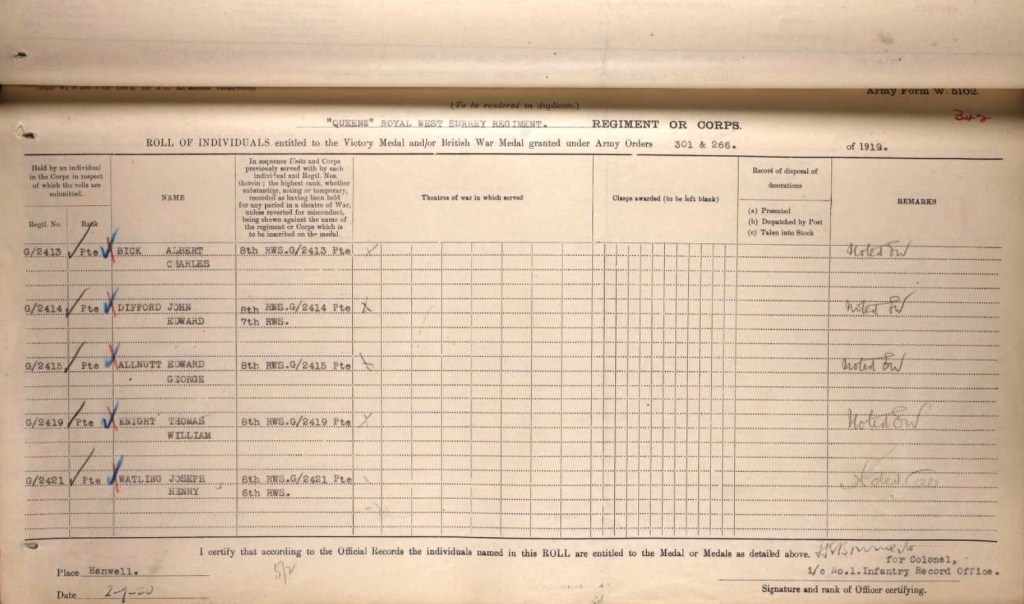

Summer 1915, C Company, The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment, Number Nine Platoon. This picture includes my 2 x great grandfather Albert Charles Bick.

On 25 September 1915 the Royal West Surrey Regiment engaged in the Battle of Loos, which resulted in 80% British casualties, including Albert, when the generals gassed their own men.

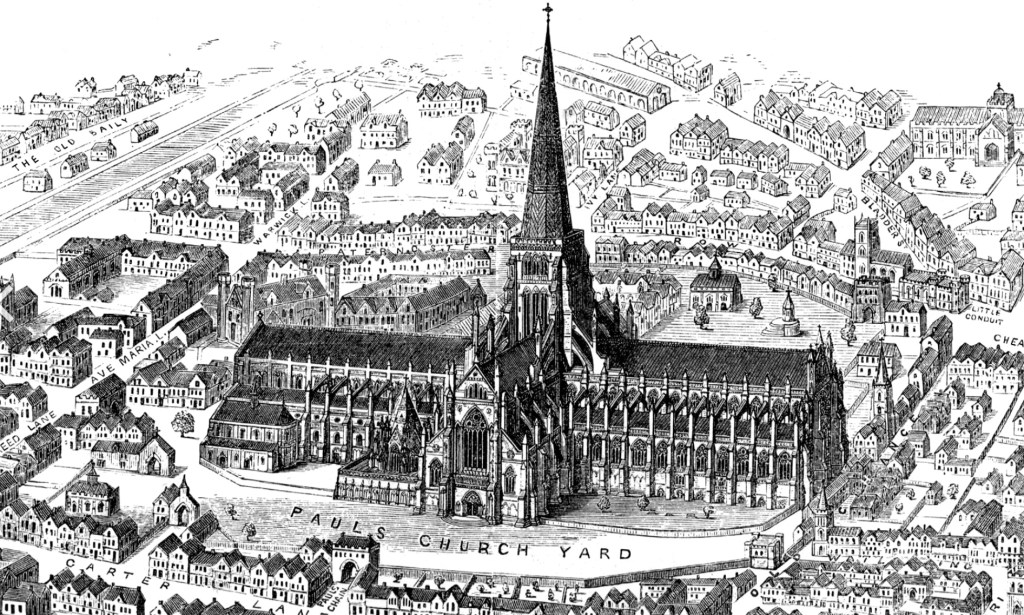

A State Lottery was recorded in 1569. The tickets were sold at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, pictured c1560.

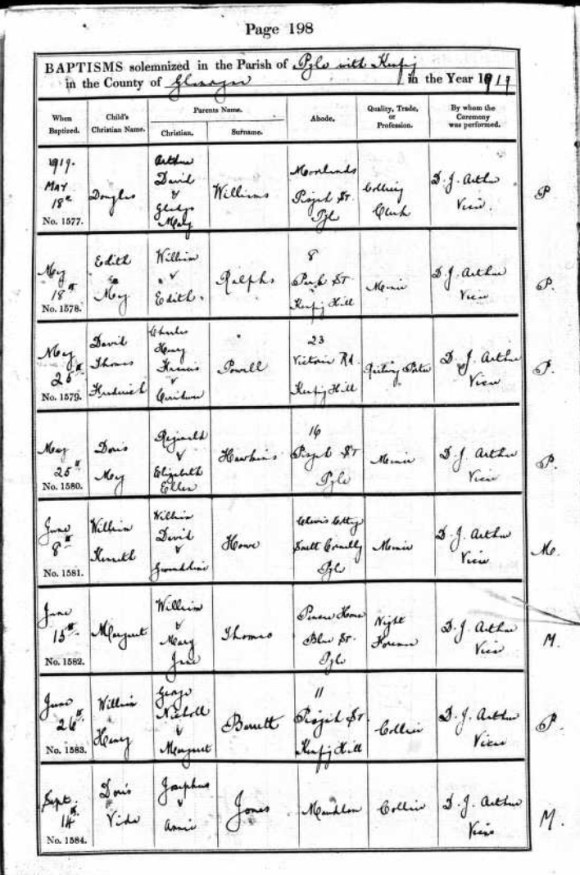

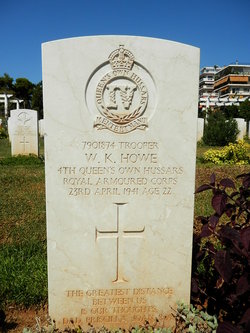

A poem written in Welsh c1920 about my 2 x great grandfather William Howe. Lines include: ‘He deserves all the praise he receives’. ‘A Christian in his warm home’. ‘William Howe is a godly saint for getting us all to pray again in the chapel with the children’. ‘We will enjoy a big feast at the Sunday School’. ‘We will sing his praises when we meet in heaven’.

My latest article for the Seaside News appears on page 36 of this month’s magazine.

I’ve traced the Bick branch of my family back to the fifteenth century. They settled in Badgeworth, Gloucestershire and lived there for hundreds of years. My branch of the family moved to London in the Victorian era, but you can still find Bicks in numerous numbers in Gloucestershire.

Unfortunately, the records for the Bicks of Badgeworth are not extensive, but I have uncovered a few nuggets of information that add details to my ancestors’ lives.

The surname Bick is of Dutch and German origin. It derives from the Middle Dutch and Middle High German word bicke meaning pickaxe or chisel. The name was associated with stonemasons and people who worked with pickaxes and chisels.

It’s likely that the Bicks arrived in Gloucestershire from the Netherlands or Germany in the early Middle Ages. My branch of the family feature in many land deeds during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These deeds indicate that they farmed land as yeomen. However, they were never described as ‘gentlemen’, which suggests that there was no link with the gentry.

Bick sons married the daughters of the following families: Meek, Fawkes, Spring, Blush, Izod and Netherton. Evocative names. These families were also of the yeomen class. The name Fawkes suggests a link to the infamous Guy Fawkes. However, Guy was from York and it is unlikely that my ancestor, Jane Fawkes, was closely related to him.

From the land, my Bick ancestors became innkeepers, running coaching inns. George was a popular name over four successive generations. George ‘the second’ – 22 October 1668 to 3 June 1738 – was an innkeeper in Badgeworth. Some of the Bicks left wills, but they are difficult to read and those that are legible contain only basic details of modest inheritances for sons and daughters.

The Bick ancestor who captured my attention was Thomas Bick, born 1575 in Badgeworth. He died in 1623 of the ‘pest’, also known as the pestilence or plague. The plague is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which mainly infects rats and other rodents who become the prime reservoir for the bacteria.

The Pestilence was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Afro-Eurasia from 1346 to 1353. The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals with profound effects for the inhabitants of the time. It also drastically altered the course of European history.

Further waves of the plague swept over Europe throughout the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries. Certain years were more blighted than others, including 1623 the year that Thomas died. That bout of the pestilence lasted until 1640. It reoccurred again in 1644–54 and 1664–67.

The 1664 to 1667 episode was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. In 1665-66 it swept through London producing the ‘Great Plague of London’. Then, in September 1666, the ‘Great Fire of London’ destroyed the city. Some people speculated that the fire killed the pestilence, although records suggest that the disease was already on the wane. My London ancestors were caught up in the ‘Great Fire of London’, but more about them in future posts.

As we know to our cost, when we abuse nature and animals we create pandemics. Our ancestors did not have the scientific knowledge to appreciate this, but we do; there is no excuse.

Along with the pestilence, our ancestors died from a range of diseases and illnesses. Here is an example from 1632 with a few definitions.

Cut of the Stone – The surgical removal of a bladder stone

French Pox – Syphilis

Jawfaln – Locked jaw

Impostume – An abscess

King’s Evil – A tuberculous swelling of the lymph glands

Livergrown – Liver disease, possibly caused by alcoholism

Murthered – Murdered

Planet – To be stricken with terror or affected adversely by the supposed influence of a planet

Purples – Purple blotches on the skin caused by broken blood vessels, indicative of an underlying illness, such as scurvy

Rising of the Lights – A condition of the larynx, trachea or lungs

Tissick – A cough

Tympany – Bloating

The saddest entry on this list, and the largest in number, is chrisomes and infants. Chrisomes refers to a baby less than a month old, which indicates that the start could often be the most dangerous period of a person’s life.

Stay safe. Wishing you well.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 31 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂