Dear Reader,

After a break since Christmas 2021, my blog is back. A week before Christmas, I became ill with Covid. That illness continued well into January. Since then, I have been catching up with my writing schedule, hence the break.

I hope you will enjoy this blog post and future content.

My latest translations, the Italian version of Operation Locksmith and the Portuguese version of Damaged: Sam Smith Mystery Series book nineteen.

In this month’s issue of Mom’s Favorite Reads…

An exclusive interview with Jennifer Shahade two-time USA Women’s Chess Champion, poker champion, author and podcaster. Plus, Author Features, Nature, Photography, Poetry, Recipes, Short Stories, Jazz Appreciation Month, and so much more!

My Recent Genealogical Research

My 3 x great grandmother Sarah Ann Cottrell was born on 24 June 1848 in St Leonard’s, Shoreditch. Aged twelve she worked as a matchbox maker, on piece rates. Sarah Ann’s father, Mathew, was a fishmonger, a decent trade, so her matchboxes brought in bonus pennies to support her mother and five siblings.

My 4 x great grandfather Mathew Cottrell was a fishmonger at Billingsgate Market. Here’s the market as Mathew would have seen it plus a description, both from the Illustrated London News, 7 August 1852.

In 1852, my 4 x great grandfather Mathew Cottrell was a fishmonger at Billingsgate Market so it seems fair to assume that his wife, Sarah, was adept at preparing fish dishes. Here’s some advice from A Mother’s Handbook, published the same year.

“Fish should be garnished with horseradish, or hard boiled eggs, cut in rings, and laid around the dish, or pastry, and served with no other vegetable but potatoes. This, or soup, is generally eaten at the commencement of a dinner.”

My 5 x great grandfather Samuel Cottrell was born on 11 July 1796 in Finsbury. After his marriage to Ann Baker he moved to Billingsgate where he worked as a fishmonger. Samuel and Ann were nonconformists, protestant dissenters. He lived in Dunnings Alley, a hotbed of dissent.

Somehow, Samuel and Ann avoided every census in the 1800s. However, the nonconformists kept detailed records, including details of Samuel’s family. These records confirm that a midwife was in attendance for all of Ann’s births along with, on occasion, a surgeon.

My 5 x great grandfather Samuel Cottrell lived a long life, 84 years. However, he struggled during his final two years. Unable to move freely, in 1878 he spent a month in Homerton Workhouse Infirmary. He signed himself out.

Two years later, Samuel spent two years in Bow Road Infirmary, pictured. Shortly after he left, a ‘Mad Russian’ murdered one of the inmates, slicing him with a knife. Within ten days Samuel was back in Homerton. He spent a further six months there, dying on 1 September 1880.

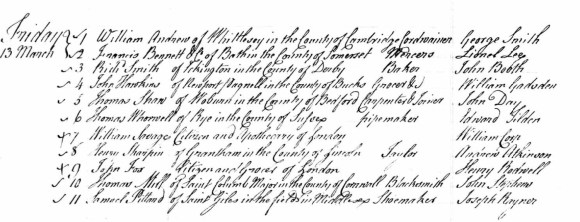

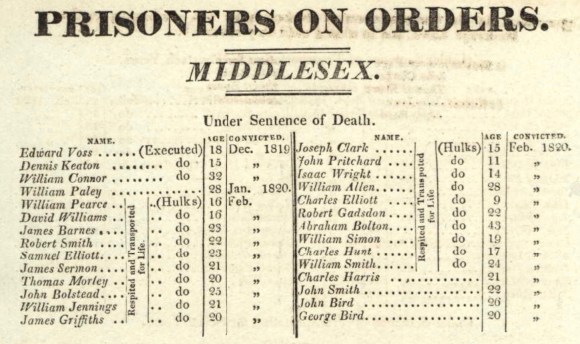

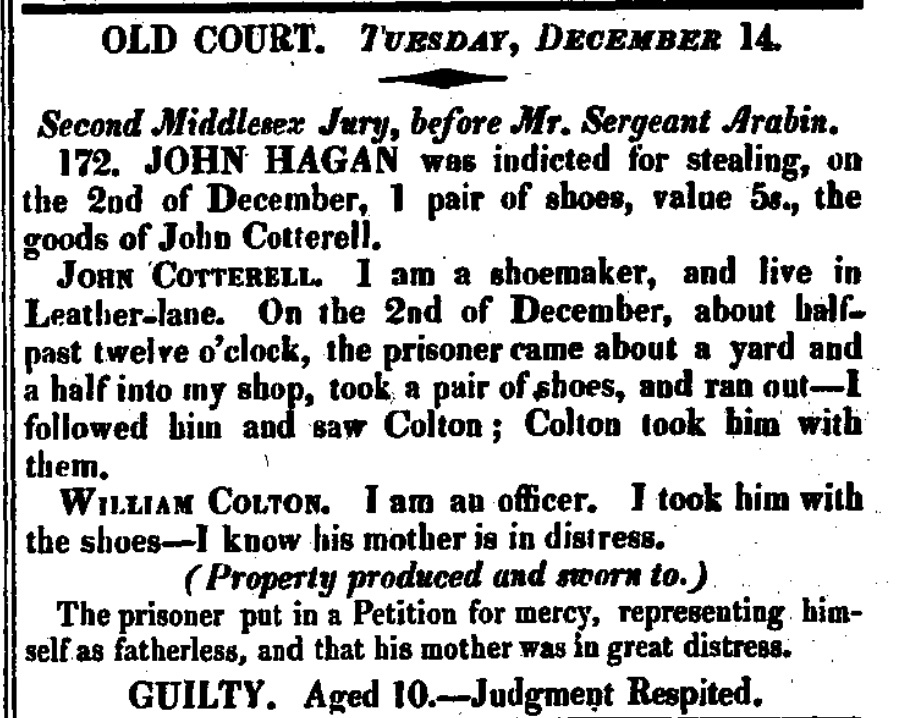

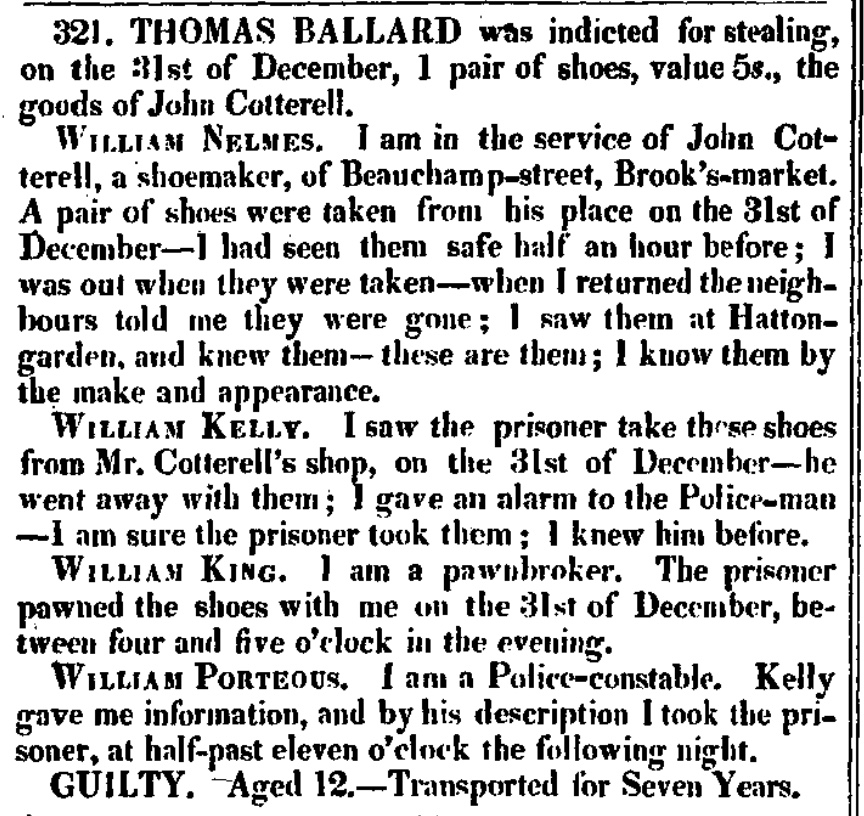

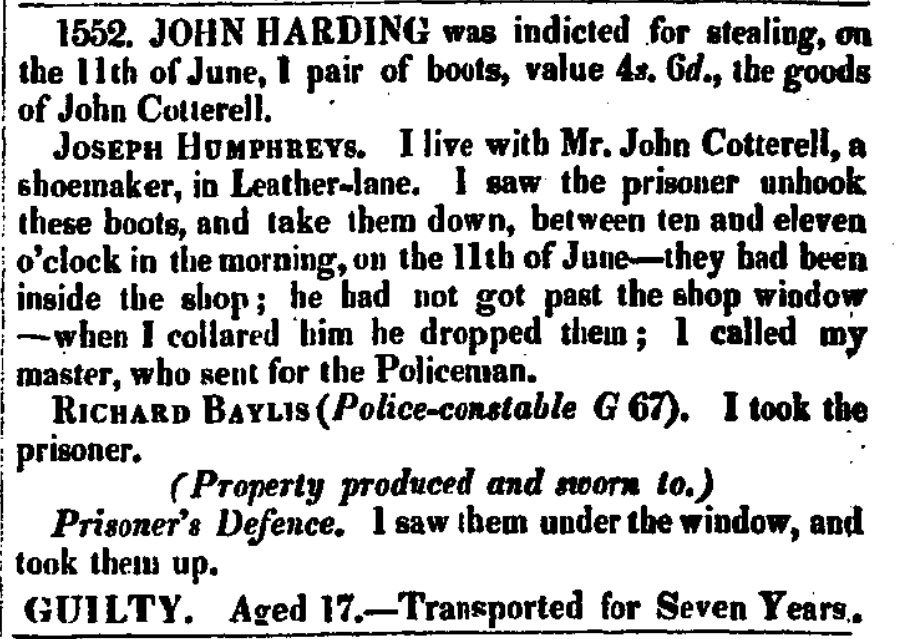

They kept stealing his shoes. My 6 x great grandfather John Cottrell was a boot maker. The Old Bailey website lists three occasions 1830 – 1832 when boys aged ten, twelve and seventeen stole his shoes. The court offered mercy to the ten year old, but the other two were transported for seven years.

St Mary Woolnoth, London. My 7 x great grandfather John Cottrell was born there on 6 Nov 1747 and baptised there on 29 Nov 1747. He ran a business as a chandler. He served on several coroner’s inquest juries and, like my Howe ancestors, was an Overseer of the Poor.

1 July 1762. An indenture belonging to my 7 x great grandfather John Cotterell. His father, also John, paid John Coleratt £80 (£8,200 today) so that he could learn the trade of tallow chandler. These indentures were standard in the 18th and 19th centuries with the names and trades added as applicable.

Apprentices were forbidden from playing cards, dice, entering taverns or playhouses, fornicating or marrying. Usually, these indentures covered a period of seven years. Little wonder that some apprentices broke the agreement and absconded.

John served his apprenticeship and in 1775 established a business on 55 Fore Street, Moorfield, selling food and household items.

As a ‘respectable member of the community’ my 7 x great grandfather John Cotterell served on five Coroner’s juries, in 1776, 1779, 1781, 1783 and 1785, each time investigating suspicious deaths in the community.

In 1785 on ‘Friday this 20th. Day of May by Seven of the Clock in the After noon twenty-four able and sufficient Men of said Liberty’ gathered at John’s house to investigate the death of Robert Jurquet. The jury concluded that being of unsound mind, with a razor, Robert Jurquet took his own life.

My 7 x great grandfather John Cotterell’s elder brother, William, was sword bearer of the City of London. The office was created in the 14th century when it was recorded that the Lord Mayor should have, at his own expense, someone to bear his sword before him:

‘a man well-bred’, one ‘who knows how in all places, in that which unto such service pertains, to support the honour of his Lord and of the City.’

Picture: George III receiving the Civic (Pearl) Sword from the Lord Mayor of London on his way to St Paul’s Cathedral, an event William probably attended.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 32 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂