Dear Reader,

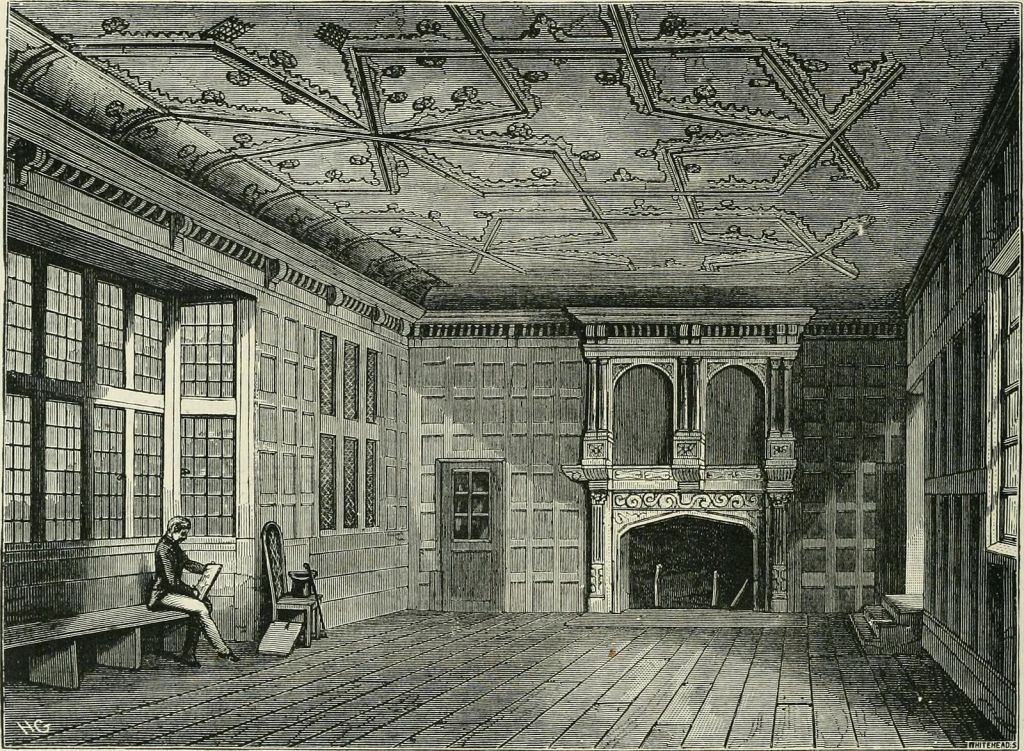

Where there’s a will there’s a murder, and my 12 x great grandfather Thomas Brereton (born 1555) was implicated 😱 The case reached the Star Chamber, who produced a report covering 106 large sheets of parchment. Was Thomas innocent or guilty? More research required…

My latest translation, the Portuguese version of A Parcel of Rogues.

My 7 x great grandfather Sandford Brereton was a Norwegian rug maker in Cheshire in the 1730s. Here’s a design from that period. I shall endeavour to discover how he became involved in that trade.

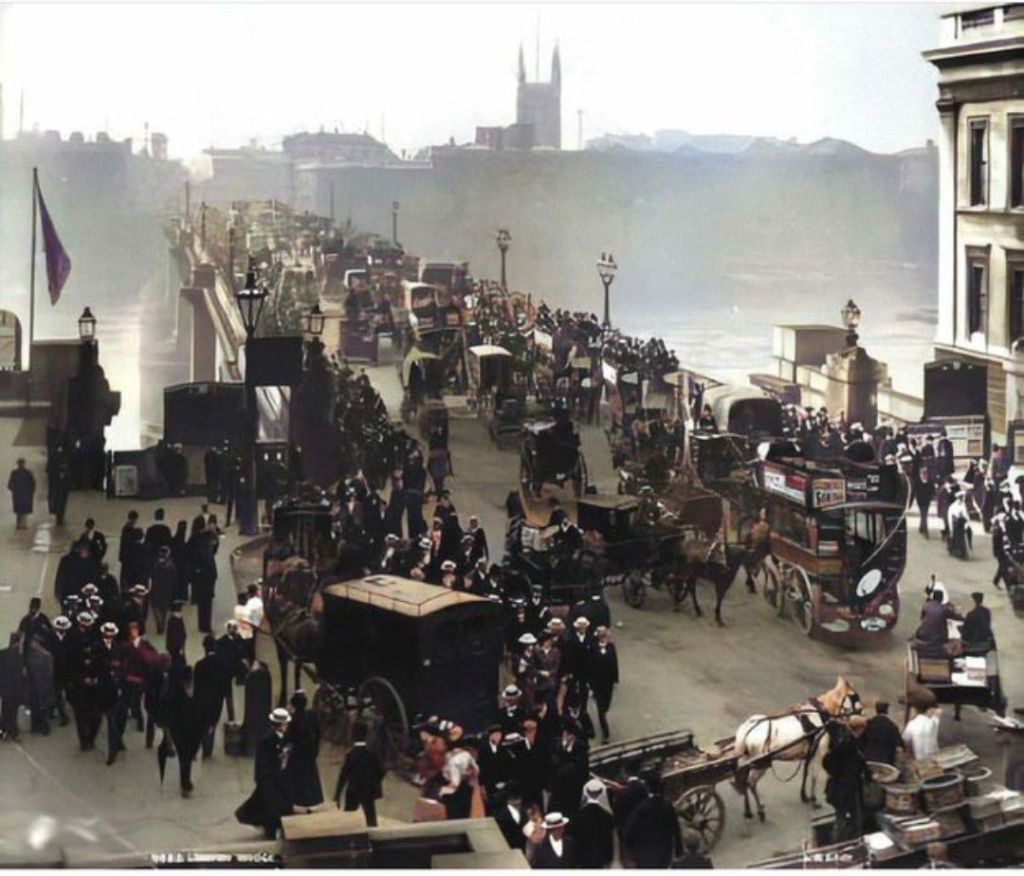

A scene familiar to my London ancestors, London Bridge looking north to south, 1890.

Many of my Welsh ancestors were agricultural labourers. A local view, taken today, and an image they would be familiar with.

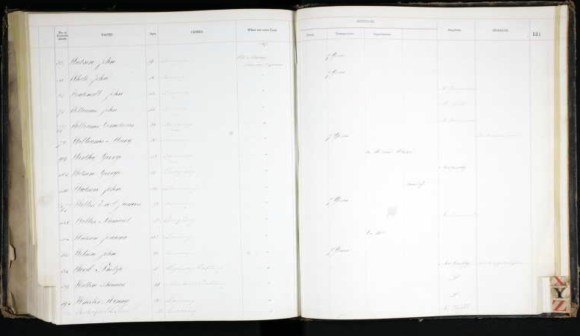

The Dent branch of my family dates back to Sir Roger Dent, born in 1438, a Sheriff of Newcastle in the north-east of England. The line continued through his son, also Sir Roger and a Sheriff of Newcastle, to Robert, William, James and Peter until we arrive in the seventeenth century with the birth of my 12 x great grandfather the Rev Peter James Dent.

Peter was born in 1600 in Ormesby, Yorkshire. In 1624, he married Margaret Nicholson the daughter of the Rev John Nicholson of Hutton Cranswick in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Margaret was baptised on 8 March 1602 at Horton in Ribblesdale, Yorkshire.

The couple had five children:

William, my direct ancestor, born 1627

Peter, born 1629

Thomas, born 1631

George, born 1633

Stephen, born 1635

Dorothy, born 1637

In 1659, Thomas emigrated to Maryland with his cousin John Dent and his nephew Nicholas Proddy.

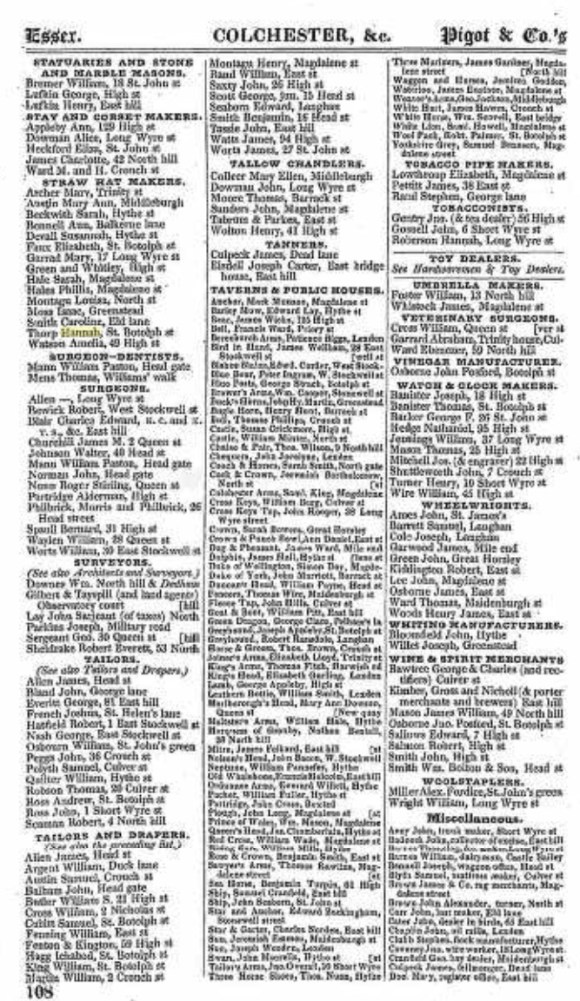

The Rev Peter James Dent was a Professor of Natural Sciences at Cambridge University and practiced medicine as an apothecary.

In addition to dispensing herbs and medicines, an apothecary offered general medical advice and a range of services that nowadays are performed by specialist practitioners. They prepared and sold medicines, often with the help of wives and family members. In the seventeenth century, they also controlled the distribution of tobacco, which was imported as a medicine.

Medicinal recipes included herbs, minerals and animal fats that were ingested, made into paste for external use, or used as aromatherapy. Some of the concoctions are similar to the natural remedies we use today.

Along with chamomile, fennel, mint, garlic and witch hazel, which are still deemed acceptable, apothecaries used urine, fecal matter, earwax, human fat and saliva, ingredients discredited by modern science.

Experimentation was the name of the game. Detailed knowledge of chemistry and chemical properties was sketchy, but if something worked, such as drinking coffee to cure a headache, it became the elixir of the day.

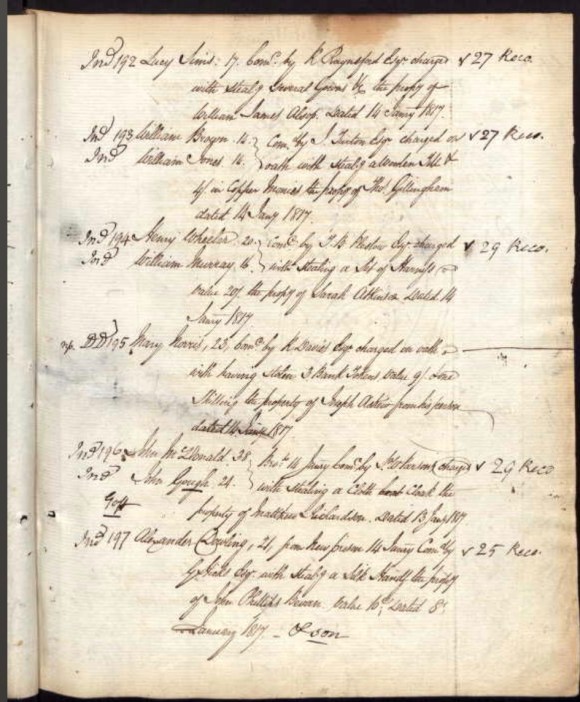

Peter left a Will, which I include here in his own words, for they offer a great insight into his life and times.

In the name of the Lord God my heavenly father and of Jesus Christ my sweet Saviour and Redeemer, Amen.

I, Peter Dent of Gisbrough in the County of York, apothecary, being in health and perfect memory, blessed be the name of God, doe make this my last will and testament the ffifth day of August one thousand six hundred seventy and one, hereby revokeing and making void all wills by me formerly made.

Ffirst, I give and bequeath my soule into the hands of the Allmighty, my blessed and heavenly Creator and Maker, fullly believing to be saved by faith in his mercy throught the meritts of Jesus Christ my alone redeemer and Saviour, my advocate, my all in all.

Item, I bequeath my body to the earth whereof it was made and the same to be buried in the parish of Gisburne aforesaid at the discrecon of my wife and friends.

Item, my will is first that my debts be paid and discharged out of my estate which being done, I give and bequeath unto my sonne Wm Dent all the estate and interest that I have in the dwelling house in Gisbrough aforesaid, wherein he, the said Wm Dent doth now inhabitt, he paying the rent and taxes lyable for the same.

Item, I give and bequeath to my wife, my house & garden and backside, which is in northoutgate called northoutgate house and garden, as alsoe the shep and stock in itt under the tollbooth and the two closes called the Turmyres and which I hold under Edward Chaloner of Gisbrough, Esq.

Item, I give and bequeath to my sonne Peter Dent halfe of all my goods belonging to my Apotheray trade or the value of them, with all the instrunts and other things belonging to itt, my debt books, all other my bookes, one great morter excepted.

Item, I give to my said sonne Will’m Dent the somme of ten pounds.

Item, I give to my sonne Thomas Dent tenn pounds.

Item, I give to my sonne George Dent the sume of tenn pouonds.

Item, I give to my sonne in law Oliver Prody my great brasse morter now in his shop as alsoe the summe of tenn pounds.

Item, I give to my daughter Dorothy Prody, wife of the said Oliver Prody, the summe of ten pounds and thirteen shilllings and foure pence to buy her a mourning ring.

Item, I give to each of my grandchildren which shall be living at my death tenn shillings as a token of my fatherly blessing upon them.

Item, I give to my daughters in law every one of them a mourneing ring about thirteene shillings foure pence a piece.

Item, I give to the poore of Ormsby five shillings.

Item, I give to Sarah & Abigail Nicholson, James Paul & Elizabeth Dugleby, each of them five shillings.

Item, I give to my sister Eliz. Prody 10s, to Kath Clark & Jane Con each of them 5s & to Eliz & Jane Prody 5s a piece.

Item, I give to (Christ)inna Dent, daughter of my brother Geo Dent, dec’ed, the sume of 10s.

Item, all the rest of my goods, moveable and unmoveable, I give & bequeath to my wife & desire her to discharge my funerall charges & expences not exceeding, but in a decent maner. And I give to the poore of Gisbrough ten pounds to be disposed as she shall think fitt.

Item, I do make my wife Margret Dent sole Executrix of this my last will and testa’nt & desireing her that my daughter Dorothy Proddy if living at my death may have after her mothers death the Northoutgate house and garden and all that belongings to it, except a lodging to my sonne George Dent in the said house dureing his batchlourship onely.

Item, I desire, nominate and appoint my cozen Thomas Proddy and my cozen Thomas Spencer to be sup’visors of this my last will and to each of them I give tenn shillings.

In witness whereof I have here unto sett my hand and seale the day and yeare above written.

Peter Dent

Sealed and published in the p(re)sence of

Ger. Ffox

Ja Wylnne

5 Oct 1671 – probate issued

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

Bestselling psychological and historical mysteries from £0.99. Paperbacks, brand new in mint condition 🙂

https://hannah-howe.com/store/