Katherine de Roet

My 20x Great Grandmother

Katherine and John of Gaunt

In the early 1370s, as a widow with several young children to look after, my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet faced an uncertain future. Then, John of Gaunt came to her aid. He placed her in the service of his new wife, Constance of Castile. Also, he offered direct financial support.

Meanwhile, Katherine’s sister, Phillipa, found herself a husband – none other than the poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, (pictured).

Why was John of Gaunt so generous towards Katherine? Events were about to take a dramatic turn…

In the autumn of 1372 the social status of my medieval ancestor, Katherine de Roet, increased significantly. The reason? She became John of Gaunt’s mistress.

A love affair between the couple had been on the cards for years. Now, with Katherine a widow, and despite the fact that John of Gaunt was married to Constance of Castile, he decided to act. Soon, she was pregnant, and attracting the displeasure of the royal court.

In 1373, my medieval ancestor, Katherine de Roet, mistress of John of Gaunt, was pregnant. Consequently, she retreated to her estate in Kettlethorpe.

Between 1373 and 1381, Katherine bore four children to John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster: three sons and a daughter.

Katherine named her first son John, after his father. Her children carried the surname Beaufort. It’s not known why that surname was chosen. My connection to Katherine stems from the Beaufort branch of my family.

In the 1370s, John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, appointed his mistress, my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet, as the governess to his daughters Philippa and Elizabeth. This was, of course, a ruse, so that John of Gaunt could remain close to Katherine.

Throughout her affair with John of Gaunt, Katherine kept a low profile, retreating to her estate in Kettlethorpe to give birth. For his part, John of Gaunt made sure that Katherine wanted for nothing. Clearly, he cared deeply for her. According to surviving documents, Katherine and John were good and loving parents. Indeed, the “Anonymous Chronicle” reports that Katherine “loved the Duke of Lancaster and the children born from him”.

In June 1377, King Edward III (pictured) died and the kaleidoscopic picture of the royal court turned again. In March 1378, my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet made public her affair with John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

Thomas Walsingham wrote in his chronicle that John of Gaunt, “casting aside every shame of man and the fear of God, allowed himself to be seen riding through the Duchy with his concubine, a certain Katherine Swynford (Katherine’s married name). Walsingham added that the people were indignant and despaired because of such scandalous behavior. In his opinion, it was because of Katherine, whom he called “a witch and a whore”, that “the most terrible curses and vile insults began to circulate against the Duke”.

Incidentally, my direct link to the kings of England begins with Edward III.

The chroniclers did not approve of my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet’s relationship with John of Gaunt. Henry Knighton wrote: “a certain foreigner Katherine Swynford lived in his wife’s house, whose relationship with him was very suspicious”.

Furthermore, the love affair disturbed members of John of Gaunt’s family, who feared its consequences. John of Gaunt himself in 1381 said that clerics and servants repeatedly warned him about the detrimental effect of his relationship with Katherine on his reputation, but he ignored them.

Considering that John of Gaunt and Katherine de Roet are my direct ancestors, I’m glad he did.

In April 1378, my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet was joined by her sister, Philippa Chaucer, wife of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, on her estate in Kettlethorpe. When able, John of Gaunt called on Katherine.

The chroniclers were still furious about Katherine and John of Gaunt’s love affair. They pointed out that Katherine’s income was greater than that of John’s wife, Constance of Castile.

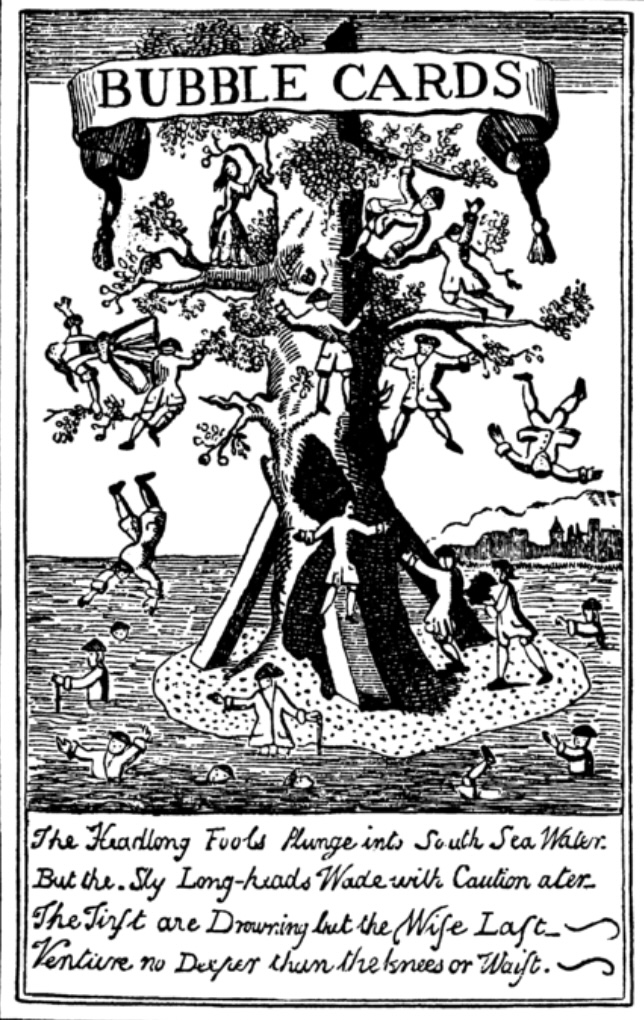

Personal and political events were coming to a head, and they exploded with the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

After the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (pictured), chronicler Thomas Walsingham stated that John of Gaunt “blamed himself for the death of [those] who had been overthrown by unholy violence” and “reproached himself for his connection with Katherine Swynford, or rather forswearing her”.

As a result, John of Gaunt ended his affair with my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet Swynford and reconciled with his wife, Constance of Castile. One of the great romances of the medieval era appeared to be over.

In 1381, my medieval ancestor Katherine de Roet returned to her estate in Kettlethorpe (pictured, Wikipedia). She remained there for twelve years, her illicit relationship with John of Gaunt apparently over.

Then fate intervened again. John of Gaunt’s wife, Constance of Castile, died and free from his political obligations, John resumed his relationship with Katherine. To everyone’s surprise, and many noblemen’s displeasure, in 1396 he married Katherine.

Discontent amongst the nobles rumbled on. Then the Pope came to John and Katherine’s aid. He recognised their marriage as valid and legitimatised all of their children. John and Katherine’s long struggle was over. They could enjoy their autumn years together, in peace.

Concluding the story of my ancestors Katherine de Roet and John of Gaunt.

Together at last, Katherine and John no doubt entertained Katherine’s sister, Philippa, and her husband Geoffrey Chaucer. Maybe Geoffrey regaled them with his latest poems.

Katherine and John’s descendants, the Beaufort family, played a major role in the Wars of the Roses with Henry VII claiming the throne through his link to Margaret Beaufort, Katherine and John’s great-granddaughter.

Through her son John Beaufort and her daughter Joan Beaufort, Katherine became the ancestor of all English kings since Edward IV.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 32 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂