Sarah Wildsmith

My 7 x Great Grandmother

Sarah and Gregory

My ancestor Sarah Wildsmith entered her thirties as a widow. She’d married at nineteen, but her husband, Philip Spooner, had languished in the debtor’s prison and died there. Could Sarah rebuild her life? Could she find a new husband?

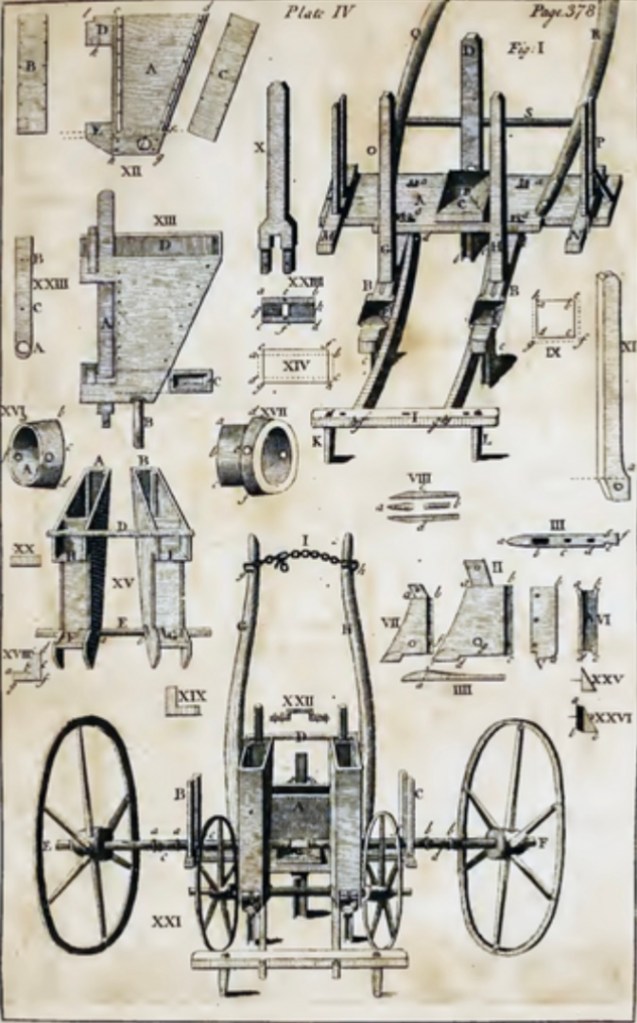

In 1731, a new man, literally, rode into town. His name: Gregory Wright. Gregory was a gentleman with a high reputation, the White Knight of the neighbourhood. He rode and tended to horses. He also ran a coaching business, transporting the citizens of London in his fine carriages.

Gregory was Sarah’s age, thirty-one. Furthermore, he was an eligible bachelor. Gregory’s coaches ferried wedding parties. Dare Sarah dream that she could become his bride?

On 6 November 1731, my ancestor Sarah Wildsmith, as Sarah Spooner widow, married gentleman, coachman and bachelor Gregory Wright. Both bride and groom were thirty-one. The marriage was a “Clandestine Marriage”, a private affair held in the environs of the ‘Mint and Mayfair Chapel’.

After weathering natural and emotional storms during the first thirty years of her life, as the wife of a prosperous and respected gentleman, Sarah could look forward to sunnier days, and the prospect of raising a family.

While my ancestor Sarah Wildsmith settled into married life with her gentleman husband Gregory Wright, the world developed around her. In 1733 the invention of the flying shuttle revolutionised weaving, and in the same year the Sugar and Molasses Act was passed to tax British colonists in North America.

In 1739-40 the weather was extreme again with a Great Frost in Britain. Also, relevant to Gregory and his coaching business, the Hawkhurst smugglers were active in the south east of England, and highwayman Dick Turpin was hanged in 1738.

On 2 September 1737 Sarah and Gregory baptised a daughter, Mary, in St Dunstan in the West, London. Then, on 7 June 1739 Sarah gave birth to William, my 6 x great grandfather. William was baptised on 8 July 1739, also in St Dunstan in the West, London. In time, William would learn from his father and join him in the family’s coaching business.

On 22 February 1752 my 7 x great grandfather Gregory Wright appeared at the London Sessions in the Old Bailey, as a witness. There, Gregory gave the following evidence.

‘Gregory Wright on his Oath Saith That On or about the Fourteenth of January Instant Two Coach Door Glasses was discovered to be Stolen out of a Coach House at the Bell and Tunn Inn, Fleet Street. Aforesaid the property of William Chamberlain, esq.’

In the court proceedings, Gregory Wright was described as a stable-keeper and coach-master living at Temple-Muse, Fleet Street, White Fryars in London.

The report continued that the thief, John Knight, tried to sell the coach glasses for twenty shillings, approximately £120 in today’s money. Knight, one of Gregory’s servants, was found guilty and sentenced to transportation.

***

A second trial, for perjury, took place on 8 April 1752 at the Old Bailey. Trials in those days were usually brief affairs, over in a matter of minutes. However, this trial received a number of witnesses and ran for some time. Details from the Old Bailey website https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

‘Thomas Ashley, was indicted for wilful and corrupt perjury on the trial of Joseph Goddard in swearing he met Simons the Jew near Brentford-turnpike, and asked him to drink a pint of beer, that he then took hold of his beard in a joke, that the Jew held up his staff and struck him, that after that he throw’d the Jew in a ditch and scratched him in the bushes, and flung a stone which fell on his head and broke it three weeks before, Sept. 11.’

Henry Simons gave evidence through an interpreter and insisted that no one had harmed him, therefore suggesting that Thomas Ashley had committed perjury at Joseph Goddard’s trial. In his evidence, Henry Simons mentioned the Rose and Crown, an inn later owned by my Brereton ancestors.

Lettice Sergeant also gave evidence and mentioned the Rose and Crown, ‘on this side of the turnpike on Smallbury-green’. She lodged there ‘from the latter end of April to Michaelmas Day.’ She stated that Ashley was drunk, that insults were offered, but that no violence took place.

Gregory Wright gave evidence. He stated, ‘I live at the Temple-Muse, Fleet-street, White Fryars, on the 21st of August last, I set out from my house after one o’clock, for Newberry-Fair by myself, till I came on the other side Hammersmith, there Mr. Pain and Mr. Mercer overtook me; we lay at Maidenhead that night; we continued in company till we came to Newberry; upon out going between the Coach and Horses, on the other side Brentford, and the Rose and Crown Alehouse, before we came at the Turnpike, I saw one man pursuing another; we might be about two hundred yards from the Rose and Crown Alehouse; I saw it was a Foreigner by his dress, that was pursued, which made me anxious to enquire what was the matter; the man behind called out stop Thief! stop Thief! which I believe to be the prisoner at the bar; when the Jew got to us, he got between Mr. Pain’s horse and mine; the drunken man, the pursuer, scrambled up near, we kept him back, the drunken man said he is a rogue and a villain; we desired he’d tell us what he had done; he said he has drank my beer and ran away, and would not pay for it; said I if that he all, let the poor man go about his business, and what is to pay, I’ll pay it; no said he, he would not, and made a scuffle to come at the Jew; I took particular notice of the Jew, he made signs holding his hand up to his beard, we said he should desist; then he (Ashley) said to me, you have robbed me, said I if this is the case you are a villain, and if you say so again I’ll horse-whip you; we stopped him there till the Jew got near to the houses at Brentford; he was very near turning the corner where the bridge is; I believe on my oath, the Jew was at least two-hundred yards off; I turned myself on my horse, half britch, to see whether he was secure, the drunken man swore and cursed, and used many bad words; there came a woman and took hold on him, she seem’d to be his wife, she desired him to go back: he fell down, then Mr. Pain said, the man (Simons) is safe enough; the last woman that gave evidence told me nothing was the matter, that the Jew did nothing to him, he had drank none of his beer, but refused it, and that he made an attempt to pull him by the beard, with that we advanced towards the Crown Alehouse, I, and I believe Mr. Pain, stopt with me; there was the woman that was examined first, I asked her what was the matter, she said no thing at all; I said if there is anything to pay for beer that that poor Jew has drank, I am ready to pay for it; she said the Jew did no harm to the man, nor drank none of his beer.’

Question: ‘Had there been a stone throw’d?’

Gregory Wright: ‘I saw none throw’d, and believe the man was so drunk that he was not able to pursue or over-take him: I saw the woman at the door the time they were running, they crossed the road backwards and forwards; the Jew kept, it may be, fifteen or twenty yards before him, I kept my eye upon them from the first of the calling out stop thief!’

On his cross examination Gregory Wright said, ‘When we first heard the alarm, we believed the Jew might be within fifty yards of the alehouse, and the others about two-hundred yards from the Rose and Crown alehouse; that they were nearer that than the Coach and Horses; that they met the Jew about two-hundred yards on this side of the Rose and Crown alehouse; that we saw no blood or mark at all on the Jew, that he made no such complaint or sign to his head, but said my beard, and sign’d to it.’

Other witnesses agreed that although the mood was threatening no violence took place and that on the whole the community were protective of Henry Simons.

Question to Mr. Wright again. ‘How came you to know of this trial to give your evidence?’

Gregory Wright. ‘I was waiting at the door of the grand jury last sessions, to find a bill against a person (the stolen coach glasses); as I was leaning over the rails, I heard Lettice Sergeant talking about the affair of this Jew; the Jew I observed looked me out of countenance; I asked his interpreter what he look’d at me so hard for, he said he believed he knew me. The woman said she was come to support the cause of this poor unhappy man, and added, that in August last there were four gentlemen coming on the road when he was pursued, and he has made all the enquirey he can to find them out, and can’t find any of them; said I what time in August? she said the 21st; I look’d at the Jew, and saw he was the same man; I ask’d his interpreter whether he was pursued by any man, he said yes, he was; I said to the woman, I know the men, by which means I was brought to the grand jury about this affair; this bill and mine were in together.’

Question to Mr. Wright. ‘Did you, or any of you, tell this witness the drunken man had thrown the Jew into the ditch?’

Gregory Wright: ‘When this witness said so, it gave me a shock: we neither of us told him so. I saw Ashley down: there were none but women at that man’s house when we came there.’

Other witnesses, including thirteen-year-old Edward Beacham supported the testimony offered by Gregory Wright, while Martha James stated that Thomas Ashley was drunk, and that ‘I never saw a man so drunk in my life.’

Verdict: Guilty.

Sentence: Thomas Ashley, to stand once in the pillory at the gate of the Sessions House for the space of one hour, between the hours of twelve and one, and imprison’d during twelve months, after which to be transported for seven years.

This trial offers an insight into the local community, the legal system and Gregory’s character. He was protective of Henry Simons and was willing to meet any expense incurred by Simons at the inn. Gregory was obviously a kind and principled man; an ancestor to be proud of.

My ancestor Sarah Wildsmith died on 8 November 1759. Her husband Gregory Wright survived her by twenty-eight years, but did not remarry.

Sarah and Gregory were held in high esteem by their community, a fact illustrated by Sarah’s burial place. She was granted the privilege of being buried in the central aisle of the church, St Bride’s, Fleet Street (pictured, Wikipedia).

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 40 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂