Sarah Wildsmith

My 7 x Great Grandmother

Sarah’s Marriage to Philip Spooner

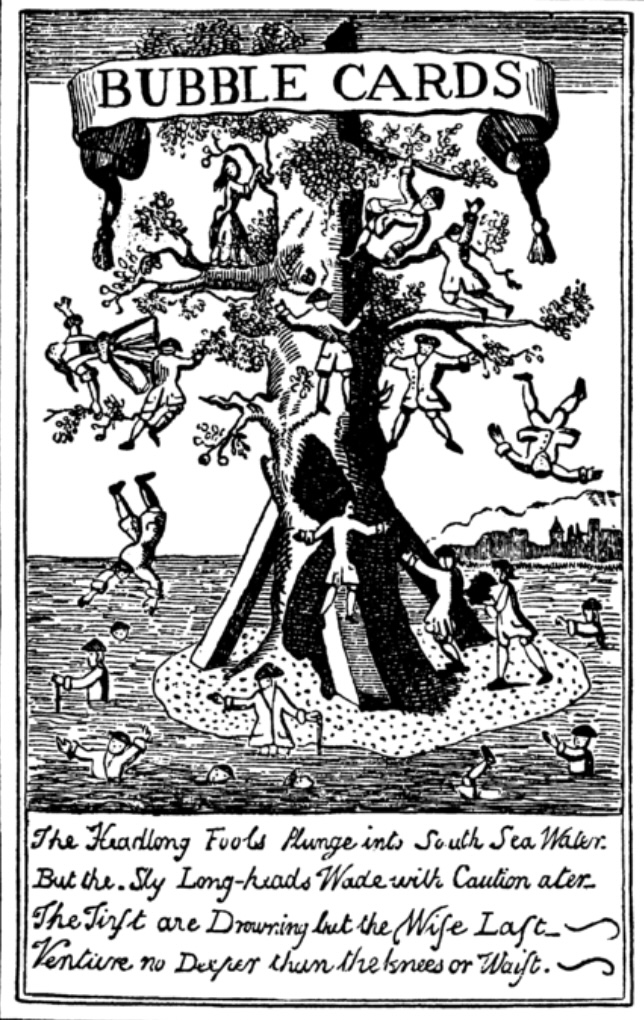

On 23 October 1719 my ancestor nineteen-year-old Sarah Wildsmith of St James’, London married twenty-four-year-old Philip Spooner, also of St James’. Sarah was from a respectable, well-to-do family, while Philip was a gentleman and a businessman. However, an air of mystery surrounded the marriage for it was a Clandestine Marriage (pictured). Why did the couple marry in such a secretive fashion?

On 23 October 1719, my ancestor Sarah Wildsmith married gentleman Philip Spooner in a Clandestine Marriage. Clandestine or Fleet Marriages took place in England before the Marriage Act of 1753. Specifically, they were marriages that took place in London’s Fleet Prison or its environs.

By the 1740s up to 6,000 marriages a year were taking place in the Fleet area, compared with 47,000 marriages in England as a whole. One estimate suggests that there were between 70 and 100 clergymen working in the Fleet area between 1700 and 1753. The social status of the couples varied. Some were criminals, others were poor. Some were wealthy while many simply sought a quick or secret marriage for numerous personal reasons.

Sarah and Philip’s marriage was recorded in the ‘Registers of Clandestine Marriages and of Baptisms in the Fleet Prison, King’s Bench Prison, the Mint and the Mayfair Chapel.’ But why did Sarah and Philip marry here? Did they wish to marry in secret, or was one of them a criminal?

The South Sea Company was a British joint-stock company founded in January 1711. Initially, the company’s stock rose in value as it expanded its operations dealing in government debt. Then, in 1720, the company collapsed. The South Sea Bubble burst sending many investors into debt. Among them was Philip Spooner, recently married to my ancestor Sarah Wildsmith. Instead of enjoying a prolonged honeymoon, Philip found himself in the debtor’s prison, and Sarah found herself a wife in name only.

In 1720, after the South Sea investment bubble burst, Philip Spooner, husband of my ancestor Sarah Wildsmith, found himself in the debtor’s prison.

Debtor’s prisons were a common way to deal with unpaid debts. Destitute people who could not pay a court-ordered judgment were incarcerated in these prisons until they had worked off their debt or secured outside funds to pay the balance.

In England, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, 10,000 people were imprisoned for debt each year. However, a prison term did not alleviate a person’s debt; an inmate was typically required to repay the creditor in full before their release.

In England and Wales debtors’ prisons varied in the amount of freedom they allowed the debtor. Through his family’s financial support a debtor could pay for certain freedoms; some prisons allowed inmates to conduct business and to receive visitors while others even allowed inmates to live a short distance outside the prison, a practice known as the ‘Liberty of the Rules.’ However, some people spent thirty years or more in prison.

Unable to raise sufficient funds to cover his debt, Philip faced a bleak future. Sarah, meanwhile, could only rely on her parents and live in hope.

My ancestor, Sarah Wildsmith, faced life alone while her husband, Philip Spooner, languished in a debtor’s prison. Along with the embarrassment for the family, life in these prisons was unpleasant. Often, single cells were occupied by a mixture of gentlemen, violent criminals and labourers down on their luck. Conditions were unsanitary and disease was rife.

Many notable people found themselves in a debtor’s prison including Charles Dickens’ father, John. Later, Dickens became an advocate for debt prison reform, and his novel Little Dorrit dealt directly with this issue.

In 1729, Philip died, probably from gaol fever contracted at the prison. Gaol fever was common in English prisons. These days, we believe it was a form of typhus. The disease spread in dark, dirty rooms where prisoners were crowded together allowing lice to infest easily.

Alone, and in financial difficulties, Sarah had to regroup and rebuild her life. Showing great determination, she did.

As ever, thank you for your interest and support.

Hannah xxx

For Authors

#1 for value with 565,000 readers, The Fussy Librarian has helped my books to reach #1 on 40 occasions.

A special offer from my publisher and the Fussy Librarian. https://authors.thefussylibrarian.com/?ref=goylake

Don’t forget to use the code goylake20 to claim your discount 🙂

One reply on “Ancestral Stories #7”

All I can say is; thank God they don’t have Debtor’s prisons these days or who knows where I’d be typing this from.

LikeLiked by 1 person